A standout amongst the most crucial unexplained question in modern day science is the means by which life started. Scientists for the most part trust that simple atoms present in early planetary environments were changed over to more unpredictable ones that could have helped kick off life by the contribution of vitality from the environment.

Scientists consider the early Earth was suffused with numerous sorts of energy, from the high temperatures delivered by volcanoes to the ultraviolet radiation transmitted somewhere around the sun. A standout amongst the greatest investigations of how natural mixes could have been made on the early Earth is the Miller-Urey experiment, which demonstrated you electrical releases mimicking lightning can help make an assortment of natural mixes, including amino acids, which are basic building blocks of all life.

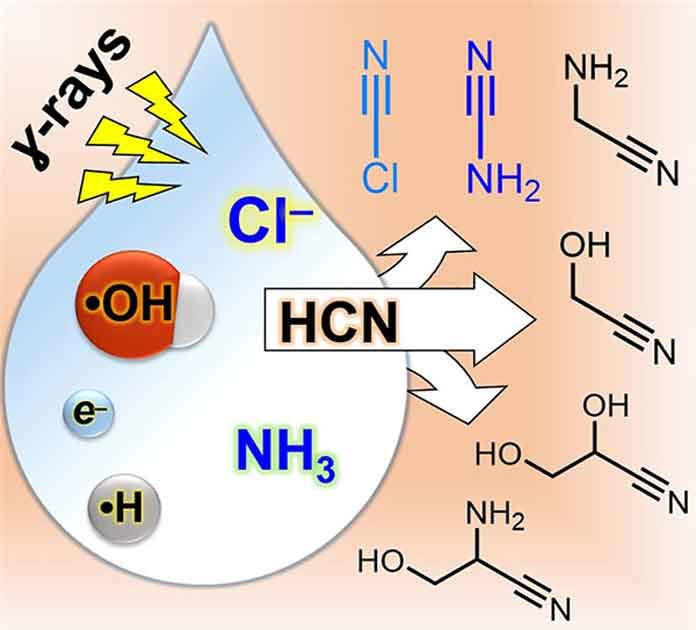

A recent study by the scientists at the Tokyo Tech shown that a variety of compounds useful for the synthesis of RNA are produced when simple compound, combined with sodium chloride, are exposed to gamma rays.

Through this work, scientists become one step closer to understanding how RNA could have arisen abiotically on early Earth. Because of its intricacy, making RNA from scratch under crude primitive solar system conditions is no simple undertaking. Biology is great in it since it has developed more than billions of years to carry out the activity with astonishing productivity.

Before life emerged, there would have been little in the environment that would have assisted in making RNA. These researchers found that sodium chloride – or common table salt – can assist in making the necessary building blocks for RNA. Sodium chloride is the chemical compound that makes the sea salty, thus it is highly likely this process could occur on primitive planets, including Earth.

The most difficult part of this work was figuring out that salt, explicitly the chloride segment, assumed a pivotal job in these responses. Normally, scientific experts disregard chloride in their reactions. At the point when physicists lead responses in water, it is almost certain probably some chloride is in there, at any rate, however more often than not it just sits inertly by as a spectator.

It regularly doesn’t assume a huge job in the reaction chemists is occupied with, it’s simply part of the foundation a great deal of the time. These specialists discovered, however, this was not the situation in their analyses, and it set aside them some opportunity to make sense of that.

What they in the long run found was that the ionizing radiation they were utilizing as the vitality source to drive their responses makes chloride lose an electron and move toward becoming what is known as a “radical”. As the name proposes, the chloride is then no longer so easygoing and turns out to be substantially more synthetically receptive.

When the chloride is enacted by gamma radiation, it is allowed to help develop other high vitality mixes which at last can enable developers to complex RNA molecules.

While these researchers haven’t yet coaxed their reactions all the way to RNA, this work shows that there is now nothing in principle which should stop this from occurring. The question now is not so much how to make all the necessary building blocks to make RNA, but how to combine them in a “warm little pond” to make the first RNA polymers.

One of the major challenges to this is understanding how other molecules, that is, other than those important for making RNA, might affect this process. The authors think this could be pretty “messy” chemistry in the sense that a lot of other molecules, which could interfere with this process, would be made at the same time.

Whether these other molecules will interfere with RNA synthesis, or even have a beneficial effect, is the future focus of these scholars’ research. Understanding very complex mixtures of chemicals are not only a challenge in origins of life research but a major challenge for organic chemistry in general.

The study is published in the journal Chemistry Select.