Strong correlational evidence suggests that involvement in the arts improves students’ academic outcomes and memory of learning events. Although it remains still unclear whether the improved outcomes are the result of general exposure to the arts, the integration of arts into content instruction, the use of effective instructional practices, or a combination of these factors.

In a new study, scientists sought to determine the effects of arts-integrated lessons on long-term memory for science content. Scientists at the Johns Hopkins University incorporated the arts into science lessons and tested if this incorporation could help low-achieving students retain more knowledge and possibly help students of all ability levels be more creative in their learning.

And scientists found the stunning results that embedding arts-based activities into conventionally taught lessons would produce learning outcomes as good as or better than traditional instruction.

Mariale Hardiman, vice dean of academic affairs for the School of Education at the Johns Hopkins University said, “Our study provides more evidence that the arts are absolutely needed in schools. I hope the findings can assuage concerns that arts-based lessons won’t be as effective in teaching essential skills.”

CREDIT

Mariale Hardiman/Johns Hopkins University

“When we talk about learning, we have to discuss memory. Children forget much of what they learn and teachers often end up reteaching a lot of content from the previous year. Here we’re asking, how exactly can we teach them correctly to begin with so they can remember more?”

All through the 2013 school year, 350 understudies in 16 fifth grade classrooms crosswise over six Baltimore, Maryland schools partook in the examination. Students were haphazardly doled out into one of two classroom sets: astronomy and life science, or environmental science and chemistry.

The investigation comprised of two sessions, each enduring three to about a month, in which understudies first took either expressions incorporated class or a custom class. In the second session, understudies got the contrary kind of class; along these lines, all understudies experienced the two sorts and every one of the eleven educators showed the two sorts of classes.

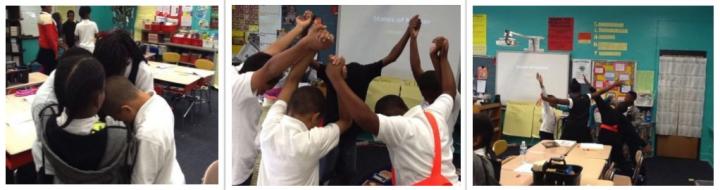

Examples of activities in expressions of the human experience incorporated classes incorporate rapping or sketching to learn vocabulary words, and designing collages to isolate living and non-living things. These exercises were coordinated in the customary classrooms with standard activities, for example, perusing passages of writings with vocabulary words so anyone might hear in a gathering and finishing worksheets.

Scientists analyzed students’ content retention through pre-, post-, and delayed post-tests 10 weeks after the study ended, and found that students at a basic reading level retained an average 105 percent of the content long term, as demonstrated through the results of delayed post-testing.

They found that students remembered more in the delayed post-testing because they sang songs they had learned from their arts activities, which helped them remember content better in the long term, much like how catchy pop lyrics seem to get more and more ingrained in your brain over time.

The research team also found that students who took a conventional session first remembered more science in the second, arts-integrated session and students who took an arts-integrated session first performed just as well in the second session. While not statistically significant, the researchers suggest the possibility of students applying the creative problem-solving skills they learned to their conventional lessons to enhance their learning.

Hardiman said, “This addresses a key challenge and could be an additional tool to bridging the achievement gap for students who struggle most to read because most conventional curriculum requires students to read to learn; if students cannot read well, they cannot learn well.”

Looking forward, Hardiman hopes that educators and researchers will put their fully-developed intervention to use to expand on their study and improve understanding of arts integration in schools.

The findings were published on Feb. 7 in Trends in Neuroscience and Education and support broader arts integration in the classroom.