Helium is the second most plentiful component in the Universe. Anticipated since 2000 as extraordinary compared to other conceivable tracers of the climates of exoplanets, these planets circling around different stars than the Sun.

It took astronomers 18 years to really distinguish it. It was difficult to spot due to the exceptionally particular observational mark of helium, situated in the infrared, out of range for the majority of the instruments utilized beforehand.

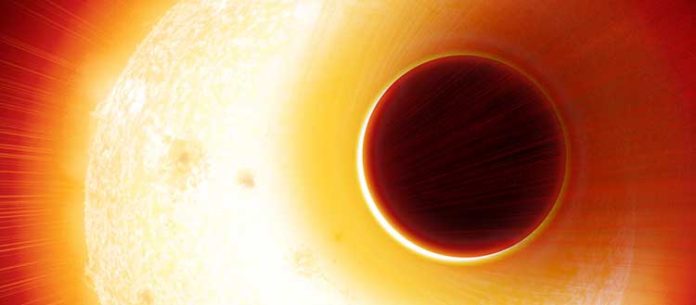

Despite its abundance, helium was only detected recently in the atmosphere of a gaseous giant by an international team including astronomers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland. Scientists observed in detail- how this gas escapes from the overheated atmosphere of an exoplanet, literally inflated with helium.

The discovery occurred earlier this year using Hubble Space Telescope observations, which were difficult to study. Team members from UNIGE, members of the National Centre for Competence in Research PlanetS, had the idea of pointing another telescope equipped with a brand-new instrument – a spectrograph called Carmenes.

A spectrograph breaks down the light of a star into its component colors, similar to a rainbow. The resolution of a spectrograph is a measure demonstrating the quantity of color that can be uncovered. While the human eye can’t recognize any color beyond red without an adjusted camera, the infrared eye of Hubble is fit for distinguishing many colors there.

This demonstrated sufficient to distinguish the shaded mark of helium. The instrument Carmenes, introduced on the 4-meter telescope at the Observatory of Calar Alto in Andalusia, Spain, is competent to recognize more than 100’000 hues in the infrared!

This high spectral resolution enabled the group to observe the position and speed of helium atoms in the upper atmosphere of a vaporous Neptune-size exoplanet, multiple times bigger than the Earth. Situated in the Cygnus (the Swan) constellation, 124 light-years from home, HAT-P-11b is a “warm Neptune” (a decent 550°C!), twenty times closer to its star than the Earth from the Sun.

Romain Allart, PhD student at UNIGE and first author of the study said, “We suspected that this proximity with the star could impact the atmosphere of this exoplanet. The new observations are so precise that the exoplanet atmosphere is undoubtedly inflated by the stellar radiation and escapes to space.”

Vincent Bourrier, co-author of the study said, “Thanks to the simulation, it is possible to track the trajectory of helium atoms: helium is blown away from the day side of the planet to its night side at over 10’000 km/h. Because it is such a light gas, it escapes easily from the attraction of the planet and forms an extended cloud all around it. This gives HAT-P-11b the shape of a helium-inflated balloon.”

Christophe Lovis, senior lecturer at UNIGE and co-author of the study said, “This result opens a new window to observe the extreme atmospheric conditions prevailing in the hottest exoplanets. The Carmenes observations demonstrate that such studies, long thought feasible only from space, can be achieved with greater precision by ground-based telescopes equipped with the right kind of instruments.”

“These are exciting times for the search of atmospheric signatures in exoplanets. In fact, UNIGE astronomers are also heavily involved in the design and exploitation of two new high-resolution infrared spectrographs, similar to Carmenes. One of them, called SPIRou, has just started an observational campaign from Hawaii, while the UNIGE Department of astronomy houses the first tests of the Near Infrared Planet Searcher (NIRPS), which will be installed in Chile at the end of 2019.”

“This result will enhance the interest of the scientific community for these instruments. Their number and their geographical distribution will allow us to cover the entire sky, in search for evaporating exoplanets.”

The results of the study, are published in Science.