About two thousand decades ago, Earth was extremely different. The water was covered in glaciers hundreds of feet thick, which stretched down over Chicago and New York City. At that time, the ocean was smaller—shorelines extended hundreds of miles farther out, and the remaining water was saltier and colder.

Additionally, it was the tail end of a 100,000-year ice age — also called the Last Glacial Maximum — and massive sheets of ice covered much of North America, Northern Europe, and Asia.

Scientists primarily studied this chilly spell in Earth’s history by looking at things like coral fossils and seafloor sediments, but now scientists at the University of Chicago may have found the first-ever direct remnants of that ocean, an actual sample of 20,000-year-old seawater, squeezed out of an ancient rock formation from the Indian Ocean.

Scientists made this discovery by exploring the limestone deposits that form the Maldives, a set of tiny islands in the middle of the Indian Ocean. The ship, the JOIDES Resolution, is specifically built for ocean science and is equipped with a drill that can extract cores of rock over a mile long from up to three miles beneath the seafloor. Then scientists either vacuum out the water or use a hydraulic press to squeeze the water out of the sediments.

The scientists were actually studying those rocks to determine how sediments are formed in the area, which is influenced by the yearly Asian monsoon cycle. But when they extracted the water, they noticed their preliminary tests were coming back salty—much saltier than normal seawater.

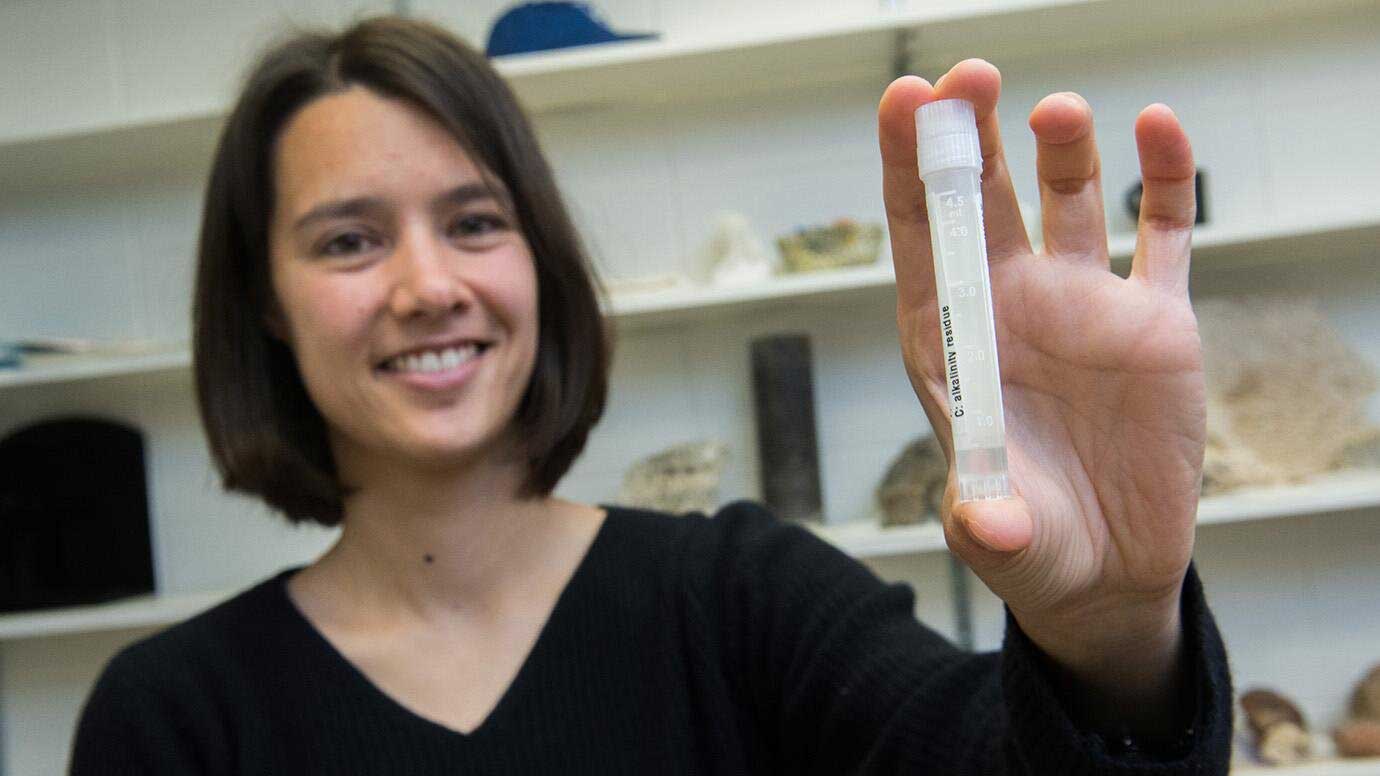

Clara Blättler, an assistant professor of geophysical sciences at the University of Chicago, said, “That was the first indication we had something unusual on our hands.”

The scientists brought the vials of water to their labs and ran a rigorous battery of tests on the chemical components and isotopes that made up the seawater. The majority of their data indicated something very similar: The water was not from today’s ocean, however, the last remains of a previous era had relocated gradually through the stone.

Scientists are keen on recreating the last Ice Age as the patterns that drove its flow, climate and weather were altogether different from today’s—and understanding these examples could reveal insight into how the planet’s atmosphere will react in the future.

Blättler said, “For example, ocean circulation is a primary player in climate, and scientists have a lot of questions about how that looked during an Ice Age. Since so much freshwater was pulled into glaciers, the oceans would have been significantly saltier—which is what we saw. The properties of the seawater we found in the Maldives suggest that salinity in the Southern Ocean may have been more important in driving circulation than it is today.”

“It’s kind of a nice connection, since Cesare Emiliani, who is widely regarded as the father of paleoceanography—reconstructing the ancient ocean—actually wrote his seminal paper on the subject here at the University of Chicago in 1955.”

“Their readings from the water align with predictions based on other evidence—a nice confirmation.”

The findings may also suggest places to search for other such pockets of ancient water.

Journal Reference

- Clara L.Blättler, John A.Higgins and Peter K.Swart, Advected glacial seawater preserved in the subsurface of the Maldives carbonate edifice, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta Volume 257, 15 July 2019, Pages 80-95 DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2019.04.030