In a new study by the NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, scientists analyzed 14 years of observations from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) to track trends in freshwater in 34 regions around the world. By merging satellite observations with data on human activities to map the locations where freshwater is changing on Earth, they found that the Earth’s wet landscapes are getting wetter and dry areas are getting drier due to a variety of factors, including water management, climate change, and natural cycles.

To put the trends in context, the scientists combined GRACE findings with precipitation data from the Global Precipitation Climatology Project; with land cover imagery and data from Landsat; with irrigation maps; and with published reports of human activities in agriculture, mining, and reservoir operations.

Matt Rodell of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center said, “This is the first time that we’ve used observations from multiple satellites in a thorough assessment of how freshwater availability is changing everywhere on Earth. A key goal was to distinguish shifts in terrestrial water storage caused by natural variability—wet periods and dry periods associated with El Niño and La Niña, for example—from trends related to climate change or human impacts, like pumping groundwater out of an aquifer faster than it is replenished.”

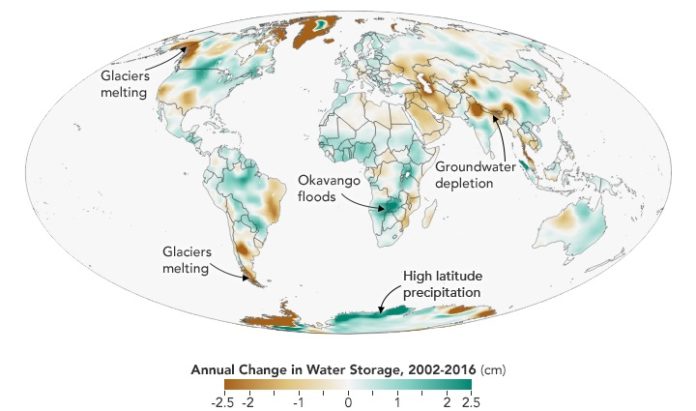

The map above depicts changes in water storage on Earth—on the surface, underground, and locked in ice and snow—between 2002 and 2016. Shades of green represent areas where freshwater levels have increased, while browns depict areas where they have been depleted.

Freshwater is found in lakes, rivers, soil, snow, groundwater, and ice. Freshwater loss from the ice sheets at the poles—attributed to climate change—has implications for sea level rise. On land, freshwater is a critical resource for drinking water and agriculture. While water supplies in some regions are relatively stable, other regions experienced increases or decreases.

Co-author Jay Famiglietti of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory said, “What we are witnessing is major hydrologic change. We see a distinctive pattern of the wetland areas of the world getting wetter—those are the high latitudes and the tropics—and the dry areas in between getting dryer. Embedded within the dry areas, we see multiple hot spots resulting from groundwater depletion.”

“While some water loss, such as melting ice sheets and alpine glaciers, is clearly driven by a warming climate, more time and data are needed to determine the driving forces behind other patterns of freshwater change. The pattern of wet-getting-wetter, dry-getting-drier during the rest of the 21st century is predicted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change models, but we’ll need a much longer dataset to be able to definitively say whether climate change is responsible for the emergence of any similar pattern in the GRACE data.”

The data offers the macro story of water mass changes on Earth. But scientists want to further check the cause of the specific global and regional trends. For instance, groundwater pumping for agricultural use is a significant contributor to freshwater depletion throughout the world, but groundwater levels are also sensitive to persistent drought or rainy conditions.

Famiglietti noted that such a combination was likely the cause of the significant groundwater depletion observed in California’s Central Valley from 2007 to 2015 when severe drought decreased groundwater replenishment from rain and snowfall at the same time that farmers pumped more water from underground.

Declining freshwater in Saudi Arabia likewise reflects rural weights. From 2002 to 2016, the district lost 6.1 gigatons every time of put away groundwater. Symbolism from Landsat satellites uncovers a dangerous development of flooded farmland over this parched scene from 1987 to the present, which harmonizes with the drawdown.

Scientists recognized huge, decade-long patterns in earthbound freshwater stockpiling that don’t have all the earmarks of being specifically identified with human exercises. For instance, in Africa’s western Zambezi bowl and Okavango Delta, water stockpiling expanded at a normal rate of 29 gigatons every year from 2002 to 2016. This wet period took after no less than two many years of dryness. Rodell trusts it was an instance of common inconstancy that happens over decades in this area of Africa.

The study is published in the journal Nature on May 16, 2018.