Snakebite is a neglected public health issue in many tropical and subtropical countries. About 5.4 million snake bites occur each year, resulting in 1.8 to 2.7 million cases of envenomings (poisoning from snake bites).

Yet the methods for manufacturing antivenom haven’t changed since the 19th century.

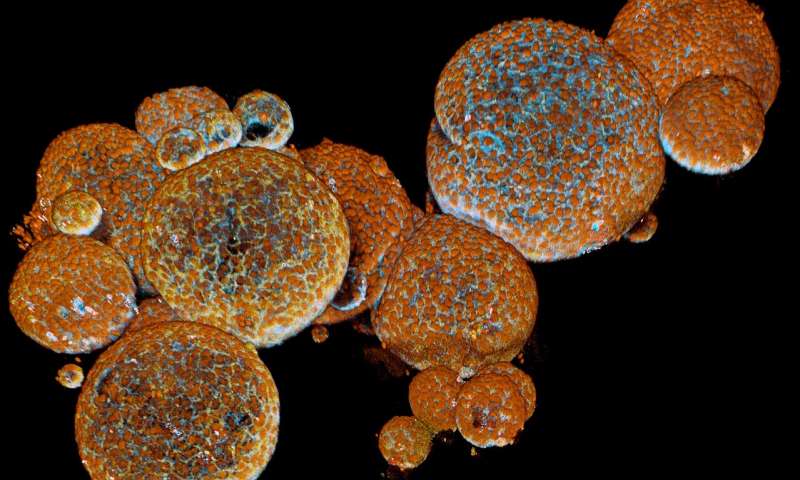

Scientists have successfully grown organoids from snake stem cells capable of producing venom. Their study could one day lead to being an effective method of creating lab-based antivenoms and developing new venom-based treatments.

Organoids are minor, three-dimensional cultured tissues that are derived from stem cells capable of self-organizing to form ‘miniature organs’ complete with numerous cell types and ready to be kept up in a lab inconclusively.

In recent years, scientists have indicated the capability of organoids in studying disease procedures and testing potential new drugs, from the advancement of mini-brains to human veins.

Presently, scientists, for the first time, have created organoids from reptilian tissue. Whenever commercialized, the group takes note of that it could be a significantly more efficient method for gathering venom when contrasted with conventional strategies for raising snakes and making their glands.

Scientists started with Cape coral snake since they knew a breeder who was able to supply some fertilized eggs. The snakes were expelled from the eggs before incubating, and small pieces of tissue were expelled from different organs and put into gels, alongside growth factors. Scientists also created the organoids from the snake liver, pancreas, and gut.

Senior author Hans Clevers of the Hubrecht Institute for Developmental Biology and Stem Cell Research at Utrecht University in the Netherlands said, “It would have been difficult to isolate stem cells from these snakes because we don’t know what they look like. But it turned out we didn’t need to. The cells soon began dividing and forming structures. The venom gland organoids grew so fast that in just one week, they were able to break them apart and re-plate them, generating hundreds of plates within two months.”

“If it could be commercialized, this method would be much more efficient than the way venom is currently produced—by raising snakes on farms and milking their glands.”

Scientists also identified a minimum of four distinct types of cells within the venom gland organoids. They confirmed that the venom peptides produced were biologically active and resembled the components of venom from live snakes.

The study is published in the journal Cell.