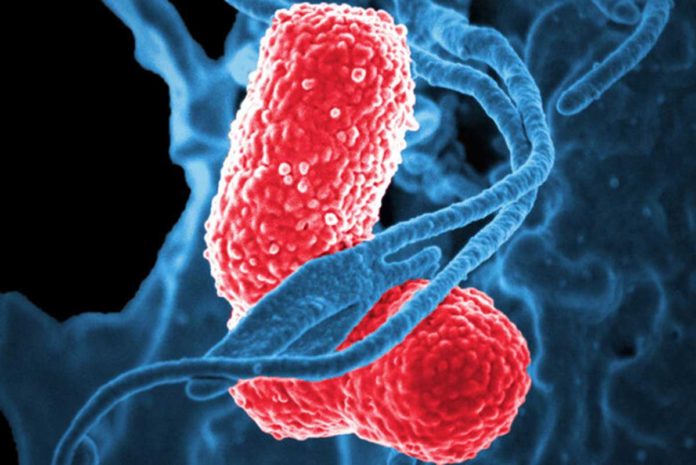

Klebsiella pneumonia is considered a nosocomial pathogen, usually infecting immunocompromised patients. It causes a variety of infections, including rare but life-threatening liver, respiratory tract, bloodstream, and other infections.

Now, scientists at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and VaxNewMo have developed and tested an effective vaccine against this superbug: Klebsiella pneumoniae. They did this by genetically manipulating a harmless form of E. coli.

The prototype vaccine is expected to protect people against a lethal infection that is hard to prevent and treat.

Co-author David A. Rosen, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of pediatrics and of molecular microbiology at Washington University, said, “For a long time, Klebsiella was primarily an issue in the hospital setting, so even though drug resistance was a real problem in treating these infections, the impact on the public was limited.”

“But now we’re seeing Klebsiella strains that are virulent enough to cause death or severe disease in healthy people in the community. And in the past five years, the really resistant bugs and the really virulent bugs have begun to merge so we’re beginning to see drug-resistant, hypervirulent strains. And that’s very scary.”

Hypervirulent strains of Klebsiella caused tens of thousands of infections in China, Taiwan, and South Korea last year, and the bacteria are spreading around the world. About half of people infected with hypervirulent, drug-resistant Klebsiella die. Two types in particular – known as K1 and K2 – are responsible for 70 percent of the cases.

Thus, scientists decided to make a vaccine against the two most common strains of hypervirulent Klebsiella. The bacterium’s external surface is covered with sugars, so the analysts structured a glycoconjugate vaccine linked with a protein that helps make the vaccine increasingly compelling.

Senior author Christian Harding, a co-founder of VaxNewMo, said, “Glycoconjugate vaccines are among the most effective, but traditionally, they’ve involved a lot of chemical syntheses, which is slow and expensive. We’ve replaced chemistry with biology by engineering E. coli to do all the synthesis for us.”

Scientists modified a harmless strain of E.coli and converted it into tiny biological factories to potentially churn out the protein and sugars needed for the vaccine. Then, by using another bacterial enzyme, they linked the proteins and sugar together.

Scientists tested the vaccine on groups of 20 mice: three doses of the vaccine or a placebo at two-week intervals. At that point, they tested the mice with around 50 bacteria of either the K1 or the K2 type. Past investigations have demonstrated that only 50 hypervirulent Klebsiella bacteria are sufficient to kill a mouse. Conversely, it takes tens of millions of classical Klebsiella – the benevolent that affects hospitalized people– to be correspondingly lethal.

Of the mice that received the placebo, 80 percent infected with the K1 type and 30 percent infected with the K2 type died. In contrast, of the vaccinated mice, 80 percent were infected with K1, and all of those infected with K2 survived.

First author Mario Feldman, associate professor of molecular microbiology at Washington University, said, “We are very happy with how effective this vaccine was. We’re working on scaling up production and optimizing the protocol so we can be ready to take the vaccine into clinical trials soon.”

“The goal is to get a vaccine ready for human use before the hypervirulent strains start causing disease in even larger numbers of people.”

Rosen said, “As a pediatrician, I want to see people get immunity to this bug as early as possible. It’s still rare in the United States, but given the high likelihood of dying or having a severely debilitating disease, I think you could argue for vaccinating everybody. And soon, we may not have a choice. The number of cases is increasing, and we’re going to get to the point that we’ll need to vaccinate everybody.”

The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.