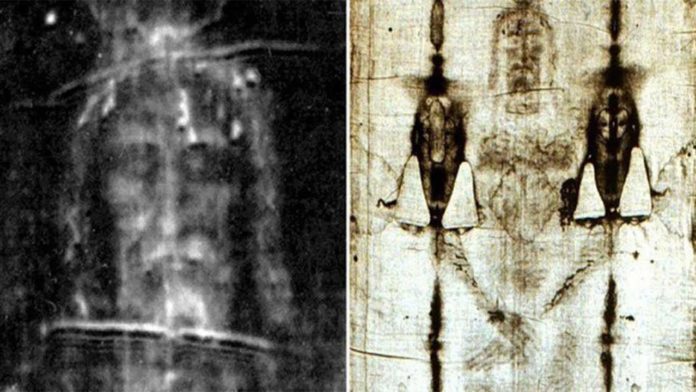

The Shroud of Turin is a centuries old linen cloth that bears the image of a crucified man. A man that millions believe to be Jesus of Nazareth. Is it really the cloth that wrapped his crucified body, or is it simply a medieval forgery, a hoax perpetrated by some clever artist? Modern science has completed hundreds of thousands of hours of detailed study and intense research on the Shroud.

It is, in fact, the single most studied artifact in human history, and we know more about it today than we ever have before. And yet, the controversy still rages.

In a new study, scientists have strapped human volunteers to a cross and drenched them in blood to prove that the Turin Shroud is real.

Scientists suggested that the mock crucifixions are the most reliable recreations yet of the death of Jesus. They are the latest in a tit-for-tat series of tests, academic rebuttals, and furious arguments over the provenance—or lack thereof—of the centuries-old religious artifact.

According to scientists, the experiment will support the hypothesis of Shroud authenticity in some new and unexpected ways.

The examination group from the Turin Shroud Center of Colorado in Colorado Springs would not remark on the crucifixion experiments previously displaying them to the American Academy of Forensic Sciences’ (AAFS’s) yearly gathering on 21 February. In any case, the theoretical portrays “an exploratory convention by which exceptional wrist and foot connection systems securely and practically suspend the male subjects on a full-size cross.”

Scientists used an image on the cloth to work out the mechanics of the crucifixion, such as where the nails were hammered in. They attempted to re-create these highlights when they set each volunteer on the cross. The male subjects were cautiously picked to compare, as intently as could reasonably be expected, to the physiology portrayed by the frontal and dorsal imprints obvious on the Shroud of Turin.

Scientists noted, “The cross and suspension system was designed to accommodate various positional adjustments of the body as appropriate.”

“Professional medical personnel were invited to not only contribute to the experimental protocol and analyses but also to ensure the medical safety of the subjects. Then, the researchers applied the blood and documented and analyzed the resulting flow patterns over the simulated, crucified subjects.”

The study also challenges previous analysis of the manner in which blood released amid an execution would have stained a wrapped body. A previous study suggested that whoever produced the stains on the shroud believed that people were crucified with their hands crossed above their heads—which historians have contested.

Matteo Borrini, the forensic scientist at Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom said, “I will be at the Baltimore meeting and will attend the talk. I’m happy to discuss this with them. At least we are discussing something physical. There is no dispute among scientists over the shroud’s origins: historical records and carbon dating show it was created in medieval times.”

The Colorado center experiment is the latest in a long line of unusual tests on the cloth. It was driven by John Jackson, a physicist who was a piece of a weeklong 1978 logical study of the shroud. Its 1981 report presumed that the shroud’s well-known picture of the bearded man—which was found in 1898 out of a photographic negative of the cloth— was that of a ‘real human type of a scourged, crucified man’ and was not delivered by an artist. The report presumed that neither chemistry nor physics could clarify how the imprints were made on the fabric, a region of vulnerability abused by the individuals who trust they were left by the bleeding body of Christ.

Other shroud researchers have pored over what little physical evidence exists, much of it left over from the 1978 study. They have analyzed pollen grains found on the material to track its movements through history and examined physical stresses placed on recovered fibers.

One of the most unusual experiments was performed by Giulio Fanti, a mechanical engineer at the University of Padova in Italy. To test Jackson’s radiation theory, in 2015 Fanti described how he suspended a mannequin wrapped in linen and then blasted its feet with 300,000 volts of electricity for 24 hours to create a coronal discharge that ionized the surrounding air and stained the covering material.

Fanti said, “Hundreds of scientists in vain [have] tried to propose hypotheses able to partially explain that body image. Arguments over the authenticity of the shroud can come down to faith.”