Scientists at the Imperial College London, for the first time in history, have demonstrated how pathogens interact with artificial human organs by using organ-on-chip technology. They hope it will help us to better understand the resulting disease and develop new treatments.

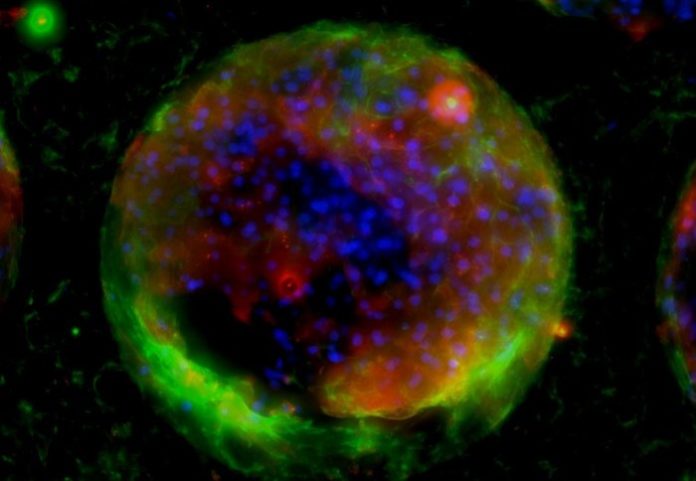

Specifically, scientists used an artificial liver and tested its response to hepatitis B virus infection. The liver was originally developed by scientists from MIT in collaboration with the University of Oxford, and biotechnology company CN Bio Innovations.

Hepatitis B virus is currently incurable and affects over 257 million people worldwide. Development of a cure has been slow because there is no model system in which to test potential therapies.

Through this technology, scientists showed that the liver-on-a-chip innovation could be tainted with hepatitis B infection at physiological levels and had comparable organic reactions to the infection as a genuine human liver, including resistant cell initiation and different markers of contamination. Specifically, this stage revealed the infection’s multifaceted methods for sidestepping inbuilt resistant reactions – a discovering which could be abused for future medication advancement.

Dr. Marcus Dorner, a lead author of Imperial’s School of Public Health, said: “This is the first time that organ-on-a-chip technology has been used to test viral infections. Our work represents the next frontier in the use of this technology. We hope it will ultimately drive down the cost and time associated with clinical trials, which will benefit patients in the long run.”

However, the technology is currently at its initial stage. Thus, scientists suggest it may, in the end, empower patients to approach new sorts of customized pharmaceutical. Instead of utilizing nonspecific cells lines, specialists, later on, could conceivably utilize cells from a genuine patient and test how they would respond to specific medications for their disease, which may make medicines more focused on and successful.

Hepatitis B is very infectious and causes liver cancer and cirrhosis. Thus, the researchers say, it was the best virus to use for the first test as its interactions with the immune system and liver cells are complex, but with devastating consequences for the tissues.

Dr. Dorner said: “Once we begin testing viruses and bacteria on other artificial organs, the next steps could be to test drug interaction with the pathogens within the organ-on-chip environment.”

The study ‘3D microfluidic liver cultures as a physiological preclinical tool for hepatitis B virus infection’ is published in Nature Communications.