The auroras indicate the impacts of a solar coronal mass ejection on the Earth’s magnetic field and atmosphere. At unexpectedly low latitudes, as far south as Italy and Texas, aurora borealis were seen in early November of this year. This latest light show was nothing compared to a massive solar storm in February 1872; it was far more dramatic. That event generated an aurora display that circled the world and saw auroras as close to the equator as Bombay and Khartoum.

Scientists from nine countries studied a major solar event, tracing its solar origin and widespread terrestrial impacts. The study reveals these storms are more common than thought. Our reliance on technology like power grids and satellites makes us vulnerable to big storms.

Designated Assistant Professor Hayakawa, the study’s lead author, explains, “The longer the power supply could be cut off, the more society, especially those living in urban areas, will struggle to cope. In the worst case, such storms could be big enough to knock out the power grid, communication systems, airplanes, and satellites. Could we maintain our life without such infrastructure?”

“It would be extremely challenging.”

Big storms like the ones in 1859 and 1921 are rare. A new study says we should also count the 1872 Chapman-Silverman storm. This storm was so strong that it affected technology, even in the tropics. Telegraphs in the Indian Ocean between Bombay and Aden were disrupted for hours, and there were issues with the landline between Cairo and Khartoum.

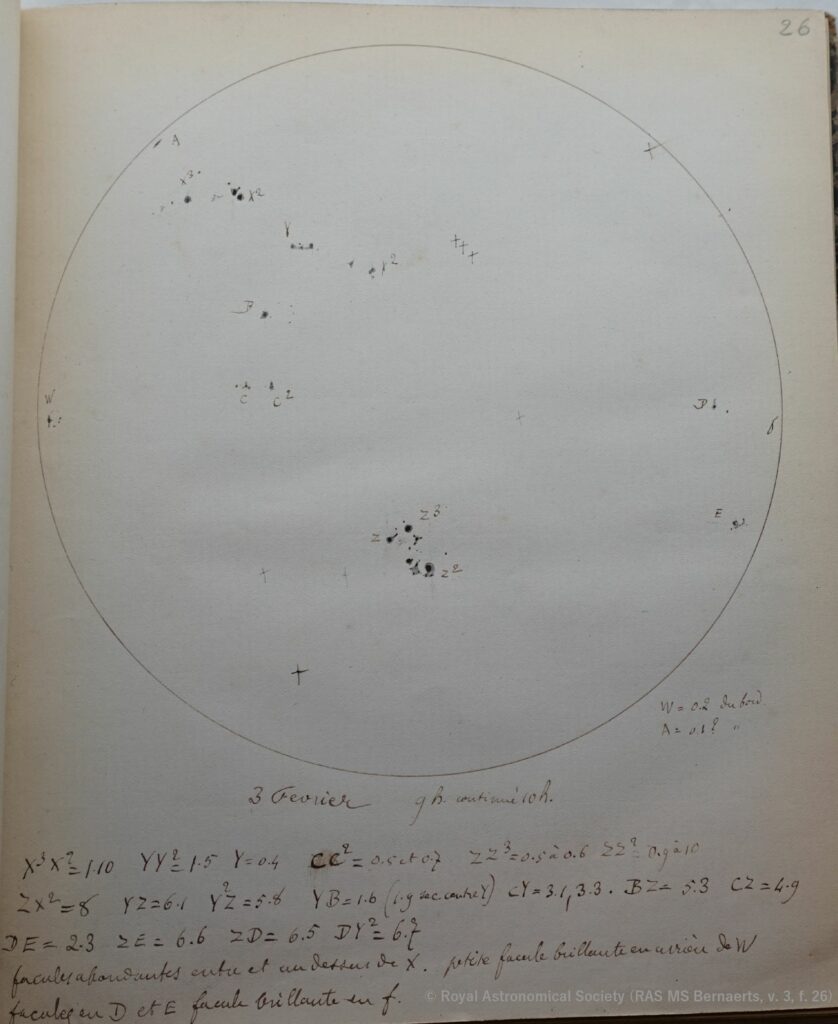

Scientists in this study used historical records and modern techniques to assess the Chapman-Silverman storm from its solar origin to its terrestrial impacts. To understand where the big storm came from, the scientists looked at old sunspot records from Belgium and Italy.

They also checked geomagnetic field measurements in places like Bombay, Tiflis, and Greenwich to see how strong the storm was. They read hundreds of accounts of colorful lights in the sky caused by the storm.

The 1872 storm was interesting because it probably started from a medium-sized but complex sunspot group near the sun’s middle. This tells us that even a medium-sized sunspot group can cause a powerful magnetic storm.

Scientists also combined records from libraries, archives, and observatories worldwide in their study. More than 700 auroral records showed that spectacular auroral displays lit up the night sky from the Arctic regions to the tropics (down to about 20° latitude in both hemispheres).

Hayakawa said, “Our findings confirm the Chapman-Silverman storm in February 1872 as one of the most extreme geomagnetic storms in recent history. Its size rivaled the Carrington storm in September 1859 and the NY Railroad storm in May 1921. This means we know that the world has seen at least three geomagnetic superstorms in the last two centuries. Space weather events that could cause such a major impact represent a risk that cannot be discounted.”

“Such extreme events are rare. On the one hand, we are fortunate to have missed such superstorms in the modern time. On the other hand, the occurrence of three such superstorms in 6 decades shows that the threat to modern society is real. Therefore, the preservation and analysis of historical records is important to assess, understand, and mitigate the impact of such events.”

This study involved a collaboration of researchers from nine countries.

Journal Reference:

- Hisashi Hayakawa, Edward W. Cliver et al. The Extreme Space Weather Event of 1872 February: Sunspots, Magnetic Disturbance, and Auroral Displays. The Astrophysical Journal. DOI 10.3847/1538-4357/acc6cc