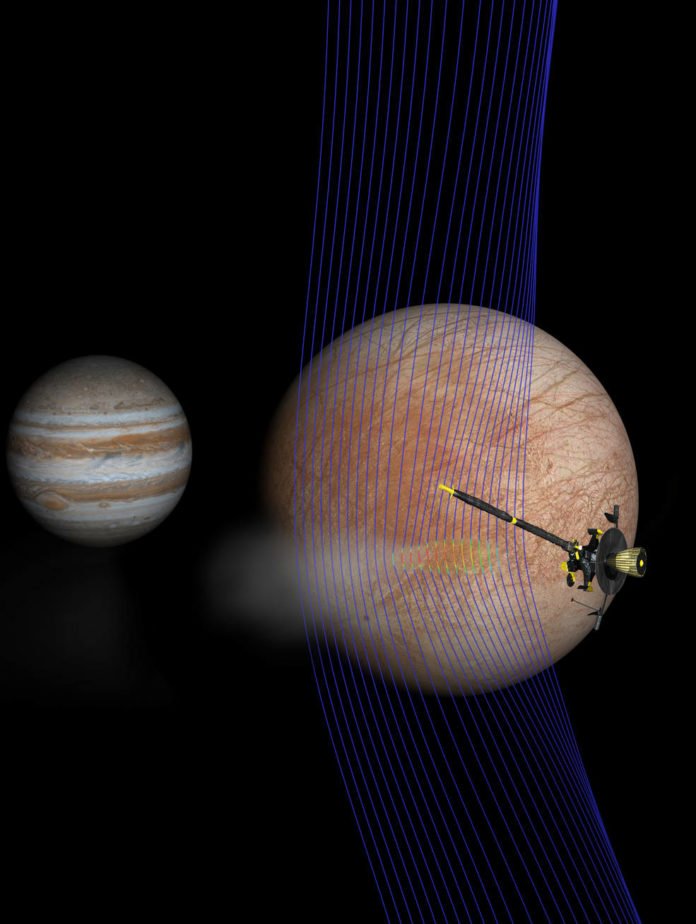

Data gathered by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft in 1997, an old mission convey new experiences to the enticing inquiry of whether Jupiter’s moon Europa has the ingredients for life. The information gives autonomous confirmation that the moon’s subsurface fluid water repository might vent crest of water vapor over its cold shell.

The data were put through new and advanced computer models to untangle a mystery — a brief, localized bend in the magnetic field — that had gone unexplained until now. A previous study based on ultraviolet images from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope suggested the presence of plumes. This new discovery used data collected much closer to the source and is considered strong, corroborating support for plumes.

Scientists examined Galileo’s data by Melissa McGrath of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California. They also presented a presentation to fellow scientists, that enlightens other Hubble observations of Europa.

The research was led by Xianzhe Jia, a space physicist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and lead author of the journal article.

Jia said, “One of the locations she mentioned rang a bell. Galileo actually did a flyby of that location, and it was the closest one we ever had. We realized we had to go back. We needed to see whether there was anything in the data that could tell us whether or not there was a plume.”

At the time of the 1997 flyby, around 124 miles (200 kilometers) over Europa’s surface, the Galileo group didn’t presume the shuttle may touch a crest ejecting from the frosty moon. Presently, Jia and his group trust, its way was serendipitous.

Galileo carried a powerful Plasma Wave Spectrometer (PWS) to measure plasma waves caused by charged particles in gases around Europa’s atmosphere. Jia’s team pulled that data as well, and it also appeared to back the theory of a plume.

But numbers alone couldn’t paint the whole picture. Jia layered the magnetometry and plasma wave signatures into new 3D modeling developed by his team at the University of Michigan, which simulated the interactions of plasma with solar system bodies. The final ingredient was the data from Hubble that suggested dimensions of potential plumes.

The result that emerged, with a simulated plume, was a match to the magnetic field and plasma signatures the team pulled from the Galileo data.

Robert Pappalardo, Europa Clipper project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California said, “There now seem to be too many lines of evidence to dismiss plumes at Europa. This result makes the plumes seem to be much more real and, for me, is a tipping point. These are no longer uncertain blips on a faraway image.”

The findings are good news for the Europa Clipper mission, which may launch as early as June 2022. From its orbit of Jupiter, Europa Clipper will sail close by the moon in rapid, low-altitude flybys. If plumes are indeed spewing vapor from Europa’s ocean or subsurface lakes, Europa Clipper could sample the frozen liquid and dust particles. The mission team is gearing up now to look at potential orbital paths, and the new research will play into those discussions.

Pappalardo said, “If plumes exist, and we can directly sample what’s coming from the interior of Europa, then we can more easily get at whether Europa has the ingredients for life. That’s what the mission is after. That’s the big picture.”