Sunscreens are products combining several ingredients that help prevent the sun’s ultraviolet (UV) radiation from reaching the skin. Two types of ultraviolet radiation, UVA, and UVB, damage the skin, age it prematurely, and increase your risk of skin cancer.

As the temperature rising, people swarm to the beach and slathers on sunscreen while splashing and swimming. Few of them use to think that the lotions and sprays are safe for marine organisms but sadly, certain chemicals in these radiation filters are bleaching the corals and killing fish.

Having concern over this, scientists at the University of Florida now have come up with a novel approach to make an environmentally safe sunscreen.

Scientists worldwide now interested in combing the world for naturally occurring chemicals that have applications in health, agriculture, and environment. Likewise, Florida scientists have discovered a more efficient way to harvest shinorine – a natural sunscreen produced by microbes called cyanobacteria.

Shinorine belongs to a family of natural products, called mycosporine-like amino acids, and is made up of two amino acids and one sugar. Many aquatic organisms exposed to strong sunlight, like cyanobacteria and macroalgae, produce shinorine and other related compounds to protect themselves from solar radiation.

The cosmetics industry is already infusing products with shinorine as a key active ingredient. Commercial supplies of shinorine come from marine red algae that grow slowly in large tidal pools that experience frequent environmental changes. That means that conventional extraction method is time-consuming and unpredictable.

In order to increase shinorine production, scientists sought a fast-growing strain of cyanobacteria that would thrive under predictable conditions. This took a lot of work! We decoded the genetic blueprints – genomes – of more than 100 varieties of cyanobacteria from marine and terrestrial ecosystems and selected one, Fischerella sp. PCC9339, to cultivate in the laboratory.

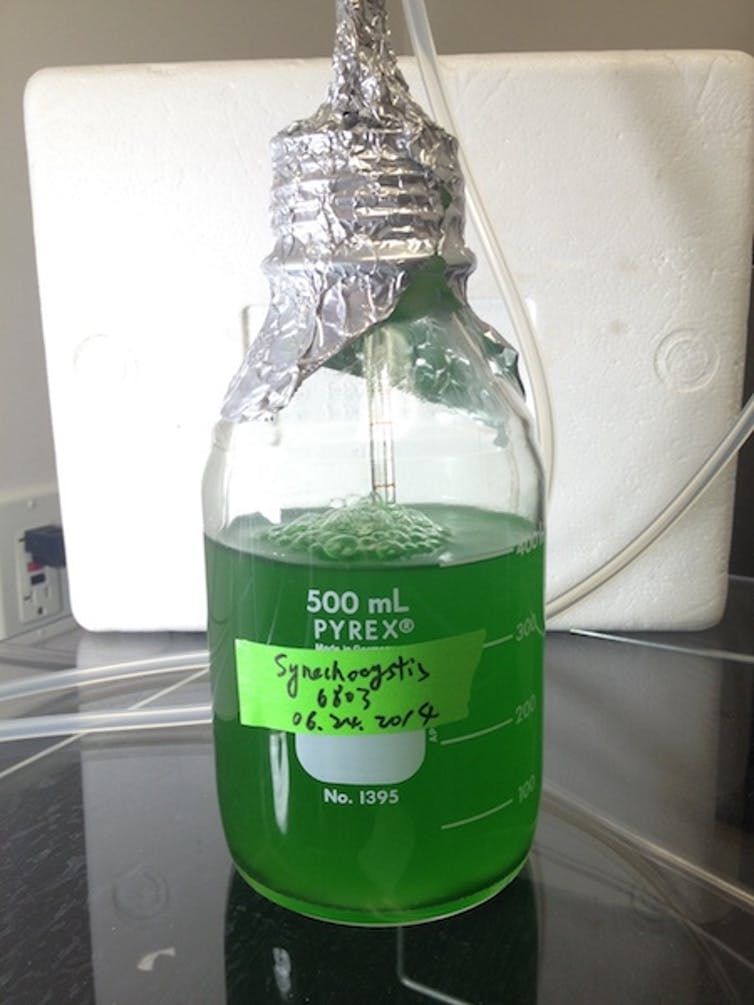

Yousong Ding, Assistant Professor of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Florida said, “To our delight, after four weeks this strain produced shinorine, but unfortunately not enough. To produce more we then transferred a set of genes that encode the instructions to make shinorine, into one freshwater cyanobacterium (from Berkeley, California), Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, which grows fast with just water, carbon dioxide, and sunlight. Using the engineered cyanobacterium, we produced a quantity of shinorine comparable to the conventional method – but we did it in just a few weeks instead of one year that’s needed to cultivate red algae.”

“By advancing the method to produce more shinorine and other UV-absorbing natural products, we hope to make “green” sunscreens more available – to protect our skin and the lives of the creatures we are so eager to see.”