We have learned in our biology classes that mitochondrial DNA comes only from the mother. But now, this theory need to be rewrite.

A new study suggests that in three unrelated families, mitochondria from the father’s sperm had been passed to the children over several generations. The study led by geneticist Taosheng Huang from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Centre shows human mitochondrial DNA can be paternally inherited.

Huang observed this while treating a sick four-year-old boy. The child, who was showing signs of fatigue, muscle pain, and other symptoms, was evaluated by doctors, and tested to see if he had a mitochondrial disorder.

When Huang ran the tests – and then ran them again to be sure – he couldn’t make sense of the results that came back. He thought there’d been a mistake.

Huang’s patient, a four-year-old boy, was carrying two different sets of mitochondrial DNA: one from his mother, as expected—and another, from his father. This was just the start. Utilizing modern DNA sequencing technology, Huang and his associates have definitively checked in a peternally-inherited mitochondrial DNA in 17 people crossing three unrelated families.

Xinnan Wang, a biologist at Stanford University said, “This is a really groundbreaking discovery. It could open up an entirely new field… and change how we look for the cause of [certain] diseases.”

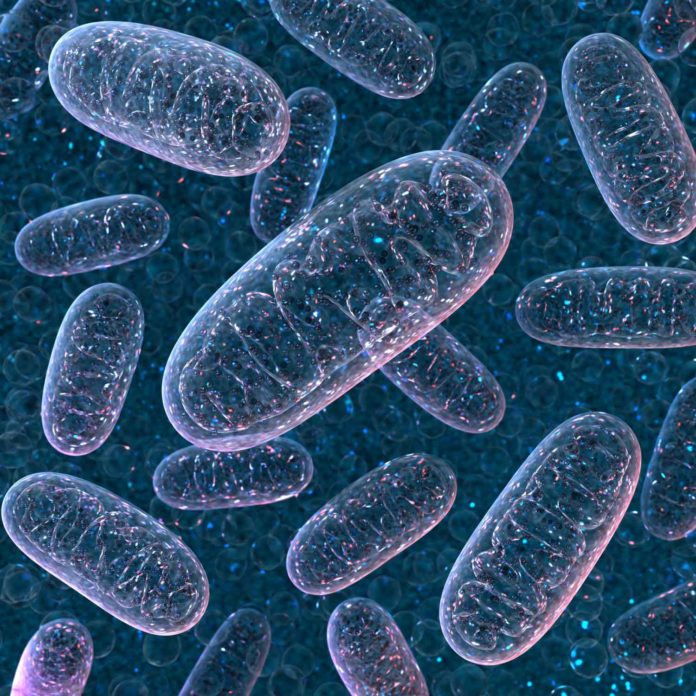

Haung noted, “We’re each a genetic mix of Mom and Dad. In the nucleus, which contains our chromosomes, this holds true. But the nucleus isn’t the only part of the cell that contains DNA. Cells contain power centers called mitochondria that also carry their own sets of DNA—and in nearly all known animals, mitochondrial DNA is inherited exclusively from the mother. This lopsided acquisition is so ingrained that researchers often analyze mitochondrial DNA to trace maternal lineages back in time.”

Most of a cell’s DNA is contained in its nucleus but mitochondria sit separately inside the cell and have their own DNA. This is because mitochondria are thought to have started as separate organisms, which entered early cells about 1.45 billion years ago and never left. They reproduce themselves and move from one generation to another by “hitching a lift” in the egg.

Amid fertilization, the dad’s sperm moves DNA into an egg, yet few or none of the sperm’s mitochondria get in. On the off chance that any do, there are mechanisms intended to obliterate them. The new research found that, in few families, the mitochondria from the dad that discovered its way into the egg were not devastated, however we don’t yet realize enough to state why.

There was likewise some proof this mitochondrial DNA from the dad may have then been replicated as the fertilized egg developed into a fetus significantly more than that from the mother.

The discovery is expected to help scientists studying the movement of humans around the planet.

Human mitochondrial DNA tends to alter very little over time because even tiny changes are often fatal so aren’t passed on to future generations. This means a person’s mitochondrial DNA is likely to be very similar to that of their distant ancestors and other people from their ethnic group.

By studying mitochondrial DNA in different populations, scientists have also been able to follow how these groups have moved around the world and even to identify a potential common female ancestor for all humans, known as “mitochondrial Eve”.

The most significant implications of these findings are staggering, because a better understanding of how mitochondria are passed on gives us a much better chance of developing treatments for mitochondrial disorders.

Their work appears today in the journal PNAS.