Students at the Rice University are developing an efficient and inexpensive uterine contraction monitor to help save the lives of mothers during labor.

A group of bioengineering understudies who call themselves Contractually Obligated composed, manufactured and customized not just a sensor to screen ladies in labor yet, in addition, a one of a kind test fix. They intend to approve the screen’s precision with the assistance of staff at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) and their patients.

In the end, the screen will probably be tried in maternity wards at doctor’s facilities in Malawi, where the Rice 360˚ Institute for Global Health is attempting to unravel the difficulties they and other low-asset clinics confront.

Leah Sherman, one of two team members who has spent time there with Rice 360˚ said, “Maternal mortality is a large problem in Malawi. We’ve seen the wards, which isn’t something you can easily forget, and we all have a passion for bringing the maternal mortality rate down. Of all of the bioengineering projects we were offered, this one seemed the most powerful and impactful for a community that is in dire need.”

“In Malawi, nurses are supposed to perform a partograph, in which they manually measure contractions every 30 minutes for 10 minutes, but the patient-to-nurse ratio is 15-to-1, so it’s not physically possible to adequately monitor all the patients. Most mothers there go unmonitored for the majority of their labor.”

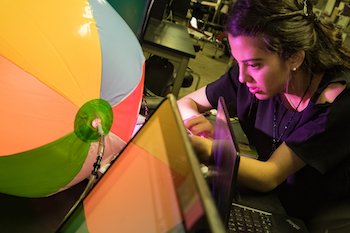

The core of the Rice gadget is a puck-like sensor that presses against the patient’s midriff and is held set up by a hearty, launderable elastic and nylon belt planned by the group to reduce the requirement for dispensable supplies and cut the danger of contamination. Contracting muscles move a layer on the sensor, which thus moves a LED within more like a photoresistor that measures the force of the light and decides the voltage yield to a microcontroller. That sends data about the withdrawals to the UI continuously.

When contractions become more frequent or indicate a risk to the patient, a box attached to the computer will light up and sound an alarm. When they’re outside of a safe physiological range for more than 10 minutes, the audible and visual cues will become more intense.

Because contractions can last between 30 seconds and three minutes, the team’s test device had to deliver a gradual increase and decrease in pressure to the sensor. A beach ball hooked to a set of microcontroller-controlled solenoids was the answer. “We started with a hand pump, but it was hard to get the nice, smooth curves you would get in real life.

Catherine Schult, one of the teammates said, “Validation will be done in parallel with devices used by UTHealth faculty in their practices, though the Rice team won’t hook up its graphical interface so attending physicians will only have access to their own monitors. Also, for some women who have higher-risk pregnancies, they often monitor them with an intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC), which is the gold standard and very accurate.”

“If our device detects 70 percent of contractions relative to those detected by that (IUPC) technology, it will be equivalent to the tocodynamometer used in the United States, which is our base goal.”

Sherman and Mildred Antwi-Nsiah, who has also worked in Malawi, were joined in the effort by teammates Aniket Tolpadi, Patricia DaSilva, Shannon Fei and Catherine Schult. All spent long days this school year at Rice’s Oshman Engineering Design Kitchen (OEDK).