Ever wondered what happens when lava and water meet? A new experiment by the University at Buffalo can answer this important question.

For the experiment, scientists cooked 10-gallon batches of molten rock and injected them with water. They found that the lava-water encounters can sometimes generate spontaneous explosions when there is at least about a foot of molten rock above the mixing point.

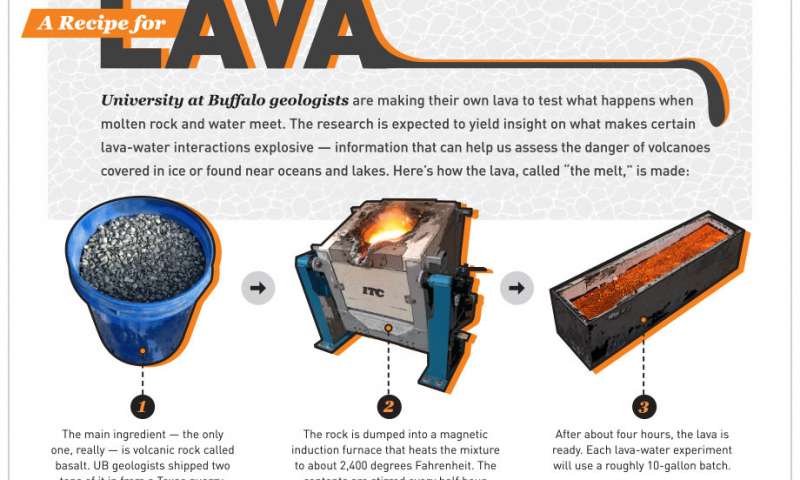

In order to make lava, scientists dump basaltic rock into a high-powered induction furnace. They heat it up for about 4 hours. When the mixture reaches a red-hot 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit, it’s poured into an insulated steel box and injected with two or three jets of water.

Then, a hammer drives a plunger into the mix to help stimulate an explosion.

The outcomes suggested that solid Earth also pointed to some preliminary trends, showing that in a series of tests, larger, more brilliant reactions tended to occur when water rushed in more quickly and when lava was held in taller containers.

Through this study, scientists wanted to shed light on the basic physics of lava-water interactions, which are common in nature but poorly understood.

Lead investigator Ingo Sonder, Ph.D, said, “If you think about a volcanic eruption, there are powerful forces at work, and it’s not a gentle thing. Our experiments are looking at the basic physics of what happens when water gets trapped inside molten rock.”

Understanding lava-water encounters at real volcanoes

In nature, the presence of water can make volcanic activity more dangerous, such as during past eruptions of Hawaii’s Kilauea and Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull. But in other cases, the reaction between the two materials is subdued.

Scientists were curious to know: “Why sometimes when lava encounters water, you see huge, explosive activity. Other times, there is no explosion, and the lava may just cool down and form some interesting shapes. What we are doing is trying to learn about the conditions that cause the most violent reactions.”

In the end, discoveries from the long haul task could enhance researchers’ capacity to evaluate the hazard that volcanoes near ice, lakes, oceans, and underground water sources pose to individuals who live in encompassing networks.

Greg Valentine, Ph.D., professor of geology at the UB College of Arts and Sciences, said, “The research is still in the very early stages, so we have several years of work ahead of us before we’ll able to look at the whole range and combination of factors that influence what happens when lava or magma encounters water.”

“However, everything we do is with the intention of making a difference in the real world. Understanding basic processes concerning volcanoes will ultimately help us make better forecasting calls when it comes to eruptions.”

The work occurs at UB’s Geohazards Field Station in Ashford, New York, some 40 miles south of Buffalo. Run by the UB Center for Geohazards Studies, the facility gives scientists a place to conduct large-scale experiments simulating volcanic processes and other hazards. In these tests, researchers can control conditions in a way that isn’t possible at a real volcano, dictating, for example, the shape of the lava column and the speed at which water shoots into it.

Sonder said, “The study did not examine why box height and water injection speed corresponded with the biggest explosions. But when a blob of water is trapped by a much hotter substance, the outer edges of the water vaporize, forming a protective film that envelops the rest of the water like a bubble, limiting heat transfer into the water and preventing it from boiling. This is called the Leidenfrost effect.”

“When water is injected rapidly into a tall column of lava, the water—which is about three times lighter than the lava—will speed upward and mix with the molten rock more quickly. This may cause the vapor film to destabilize. In this situation, the unprotected water would expand rapidly in volume as it heated up, imposing high stresses on the lava, he says. The result? A violent explosion.”

“In contrast, when water is injected slowly into shallower pools of lava, the protective vapor film may hold, or the water may reach the lava’s surface or escape as steam before an explosion occurs.”

The National Science Foundation funded the study.

In addition to Sonder, UB co-authors included Andrew G. Harp, Ph.D., who contributed to the project as a UB geology Ph.D. candidate and is now a lecturer in geological and environmental sciences at the California State University, Chico; Alison Graettinger, Ph.D., who contributed to the project as a UB geology postdoctoral researcher and is now an assistant professor of geosciences at the University of Missouri-Kansas City; Pranabendu Moitra, Ph.D., who contributed to the project as a UB geology postdoctoral researcher and is now a postdoctoral research associate in the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona; and Greg Valentine, Ph.D., professor of geology in the UB College of Arts and Sciences and director of the Center for Geohazards Studies at UB. Ralf Büttner, Ph.D., and Bernd Zimanowski, Ph.D., of the Universität Würzburg in Germany also contributed.

Journal Reference

- Sonder, I., Harp, A. G., Graettinger, A. H., Moitra, P., Valentine, G. A., Büttner, R., & Zimanowski, B. (2018). Meter-Scale Experiments on Magma-Water Interaction. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 123(12), 10,597-10,615. DOI: 10.1029/2018JB015682