Researchers at Tokyo Tech have found a quality that seems to assume a fundamental job in pheromone detecting. The gene is moderated crosswise over fish and mammals and more than 400 million years of vertebrate development, demonstrating that the pheromone sensing system is significantly more antiquated than already accepted.

This revelation opens new ways of an investigation into the origin, evolution, and capacity of pheromone signaling.

Most land-dwelling vertebrates have both an olfactory organ that recognizes odors and a vomeronasal organ that identifies pheromones, which evoke social and sexual practices. It has generally been trusted that the vomeronasal organ evolved when vertebrates progressed from living in water to living on land. New research by Masato Nikaido and associates at Tokyo Tech, in any case, recommends that this organ might be significantly more established than already accepted.

The vomeronasal organ contains receptors in the V1R protein family that are pivotal for pheromone detection. Nikaido et al. distinguished a gene, ancV1R, that encodes a previously unknown member of the V1R family. However, unlike other V1R genes, ancV1R is present not only in land-dwelling vertebrates but also in some fish lineages, indicating that it has been conserved over 400 million years of vertebrate evolution. According to Nikaido, this finding was “quite surprising, as this represents the first discovery of a V1R family gene shared between fish and mammals.”

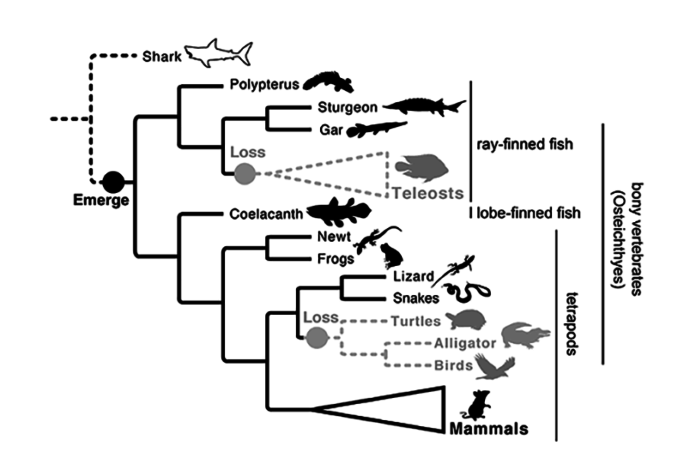

The creators recognized ancV1R in 56 of 115 vertebrate genomes. Strikingly, the loss of ancV1R in some vertebrate lineages, for example, higher primates (counting people, chimpanzees, and gorillas), cetaceans (counting whales and dolphins), birds, and crocodiles, relates with the loss of the vomeronasal organ in these ancestries (Fig. 1). The discoveries recommend not just that ancV1R might be a vital component of the vomeronasal organ, yet in addition that this organ originates before the change of vertebrates to land, opening another road of examination into its origin.

Nikaido noted, “ancV1R is also unusual in that it is expressed in most vomeronasal sensory neurons. In contrast, other V1R proteins follow a “one neuron–one receptor” rule, with only a single receptor being expressed in each neuron. This further demonstrates the importance of ancV1R in pheromone sensing. It will be fascinating to further investigate how these patterns of expression are regulated and to determine their functional role in chemosensory signaling.”

The study is published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.