It makes sense that guardians who physically or candidly mishandle their youngsters do them enduring harm, in addition to other things by undermining their capacity to believe others and precisely read their feelings.

Yet, shouldn’t something be said about the offspring of guardians who encounter basic, regular clash?

New research distributed in the ebb and flow issue of the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships demonstrates that the enthusiastic handling of these kids, as well, can be influenced – possibly making them over-watchful, on edge and defenseless against mutilating human communications that are unbiased in tone, rattling them relationally as grown-ups.

The study is also one of the first to measure the impact of temperamental shyness on the children’s ability to process and recognize emotion.

Alice Schermerhorn, an assistant professor in the University of Vermont‘s Department of Psychological Sciences said, “The message is clear: even low-level adversity like parental conflict isn’t good for kids. If their perception of conflict and threat leads children to be vigilant for signs of trouble, that could lead them to interpret neutral expressions as angry ones or may simply present greater processing challenges.”

In the examination, 99 nine-to-eleven-year-olds were partitioned into two gatherings in view of a progression of mental appraisals they took that scored how much parental clash they encountered and the amount they felt the contention undermined their folks’ marriage.

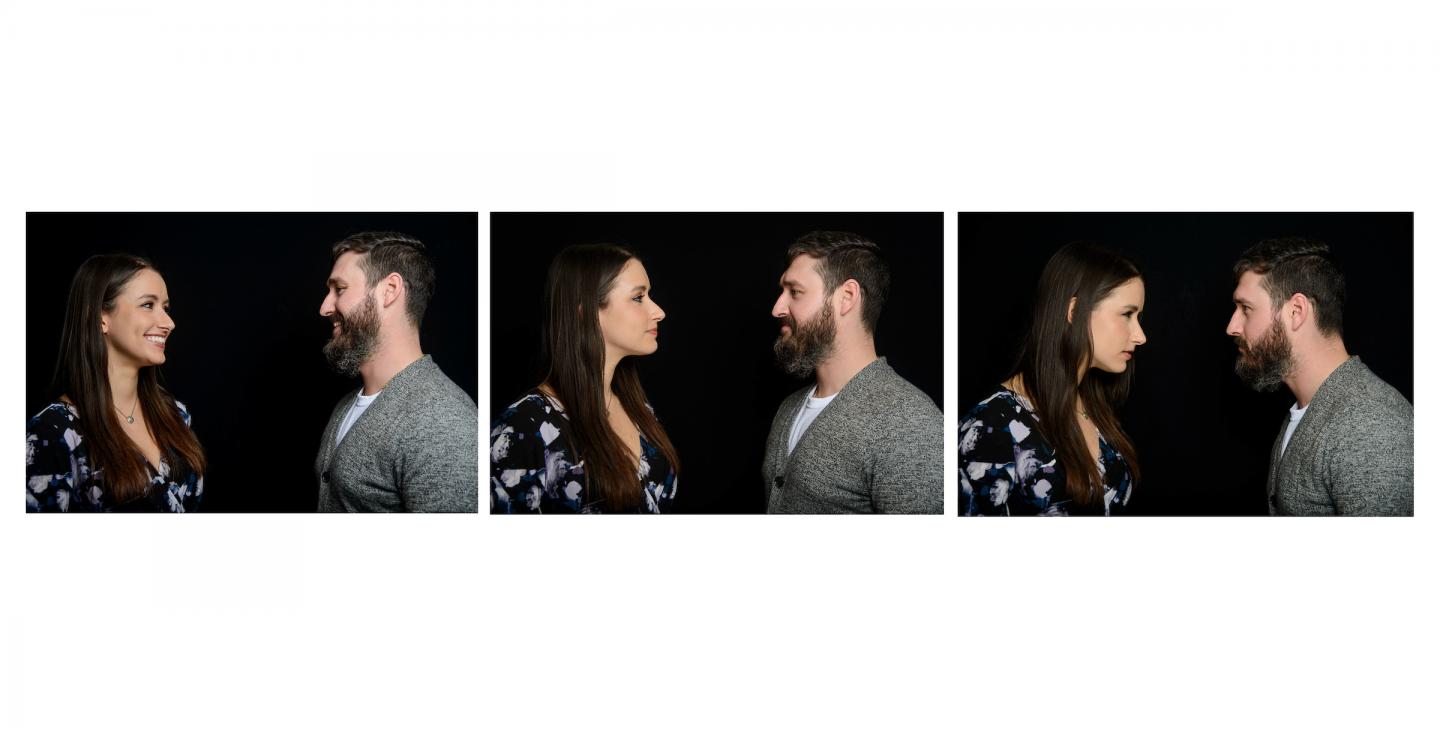

Kids have then demonstrated a progression of photos of couples occupied with cheerful, irate or impartial collaborations and requested to pick which class the photographs fit.

Youngsters from the low clash homes reliably scored the photographs precisely. Those from high clash homes who encountered the contention as a danger could precisely distinguish the cheerful and furious couples, yet not those in unbiased postures – erroneously understanding them as either irate or upbeat or saying they didn’t know which classification they fit.

Schermerhorn sees two conceivable understandings of the outcomes.

The error may inferable from hypervigilance.

Alternatively, it could be that neutral parental interaction may be less significant for children who feel threatened by their parents’ conflict. The shy kids in the examination, who were distinguished by means of a poll given to the moms of the investigation subjects, were not able effectively to recognize couples in nonpartisan postures, regardless of whether they were not from high clash homes.

Timidity additionally made them more defenseless against parental clash. Youngsters who were both modest and felt threated by their folks’ contention had an abnormal state of incorrectness in recognizing impartial communications.

Schermerhorn said, “Parents of shy children need to be especially thoughtful about how they express conflict.”

The research results are significant, Schermerhorn said, for the light, they shed on the impact relatively low-level adversity like parental conflict can have on children’s development.

Either of her interpretations of the research findings could spell trouble for children down the road.

“One the one hand, being over-vigilant and anxious can be destabilizing in many different ways,” she said.

“On the other, correctly reading neutral interactions may not be important for children who live in high conflict homes, but that gap in their perceptual inventory could be damaging in subsequent experiences with, for example, teachers, peers, and partners in romantic relationships.”

“No one can eliminate conflict altogether,” she said, “but helping children get the message that, even when they argue, parents care about each other and can work things out is important.”