Tooth replacement in piranhas is unusual: all teeth on one side of the head are lost as a unit, then replaced simultaneously. Be that as it may, no museum specimens have ever demonstrated this hypothesis to be valid, and there’s no documentation of piranhas missing an entire block of teeth.

Now, scientists at the University of Washington have affirmed that piranhas and their plant-eating cousins, pacus- indeed lose and regrow all the teeth on one side of their face multiple times throughout their lives.

Senior author Adam Summers, a professor of biology and of aquatic and fishery sciences at UW Friday Harbor Laboratories on San Juan Island said, “I think in a sense we found a solution to a problem that’s obvious, but no one had articulated before. The teeth form a solid battery that is locked together, and they are all lost at once on one side of the face. The new teeth wear the old ones as ‘hats’ until they are ready to erupt. So, piranhas are never toothless even though they are constantly replacing dull teeth with brand new sharp ones.”

Scientists pieced together the unlikely story of how piranhas and pacus lose and replace their teeth. With new teeth waiting in the wings, the fish are never missing a full set of pearly whites.

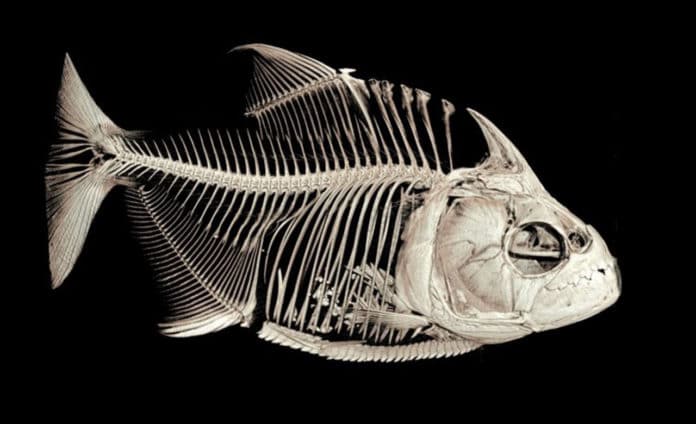

By using advanced imaging techniques, scientists were able to see clearly the contours and topography of the teeth inside various fish specimens. They found that the teeth on each side were interlocked together, forming two strong blocks within each mouth.

Lead author Matthew Kolmann, a postdoctoral researcher at George Washington University who started this work with Summers as a researcher at Friday Harbor Labs, said, “When one tooth wears down, it becomes hard to replace just one. Once you link teeth together, if one wears too much, it becomes like a missing link in an assembly line. They all have to work together in a coordinated way.”

“The interlocking teeth likely benefit the fish, allowing them to distribute stress over all of their teeth when chewing. The tradeoff of having to lose an entire set of teeth all at once is perhaps worth it over the course of their lives.”

Co-author Karly Cohen, a UW biology doctoral student, said, “With interlocking teeth, the fish go from having one sharp tooth that can crack a nut or cut through the flesh to a whole battery of teeth. Among piranhas and pacus, there’s a lot of diversity in how the teeth lock together, and it seems to relate to how the teeth are being used.”

Scientists used the best state-of-the-art analysis investigation strategies to examine in detail the examples of many piranhas and pacus. They CT-checked 93 specimens of 40 different species, digitizing the bones and connective tissues for high-resolution, 3D examination. They additionally stained the tissues of fish to perceive how teeth develop and incorporated hereditary information about each species to comprehend their evolutionary associations with one another.

These techniques showed a clear pattern of tooth replacement in nearly every piranha and pacu fish they examined. Scientists also teased new information out of dozens of fish specimens that sat on the shelves of natural history museums around the country.

Kolmann said, “The motivation for this work came out of an effort to take those collections and come up with new ways of learning about the biology of fish.”

The other co-authors are Katherine Bemis of Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Frances Irish of Moravian College; and L. Patricia Hernandez of George Washington University.

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Clyde D. & Lois W. Marlatt, Jr. Fellowship and Friday Harbor Laboratories.

The study is published in the journal Evolution and Development.