Coral reefs are the most diverse of all marine ecosystems. They teem with life, with perhaps one-quarter of all ocean species depending on reefs for food and shelter.

Human impact on coral reefs is significant. Coral reefs are dying around the world. Damaging activities include coral mining, pollution (organic and non-organic), overfishing, blast fishing, the digging of canals and access into islands and bays.

In other words, now, it has become quite difficult and expensive to observe coral reefs, particularly remote, hard-to-access locations such as the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI). In any case, a University of Hawai’i (UH) at Mānoa scientist and her colleagues may have discovered a baffling natural wonder that can enable us to observe coral reef health from space.

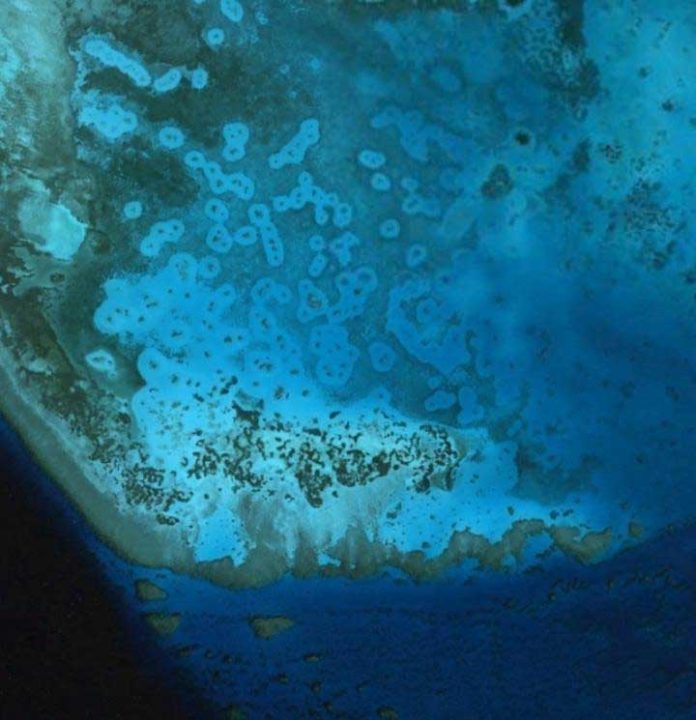

Patches of coral reef are frequently encompassed by exceptionally huge ‘halos’ of bare sand that are hundreds to thousands of square meters. Beyond these halos lie lush meadows of seagrass or algae.

Two recently published studies and a third feature story led by Elizabeth Madin, an assistant research professor at the Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) in the UH at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, shed light on these enigmatic features that are visible from space.

CREDIT

Copyright: DigitalGlobe.

Scientists observed reef halos for decades and clarified their presence as the consequence of fish and invertebrates, who ordinarily hide away in a patch of coral, wandering out to eat algae and seagrass that is spread over the sorrounding seabed. Be that as it may, what concerns the predators most is the safety of these smaller animals, that has long been thought to explain why the cleared area is circular.

In the study, scientists uncovered that there is more to the story, and further that these features may be useful in observing aspects of reef ecosystem health from space. During one of the studies, scientists found that no-take marine reserves, where fishing is prohibited, dramatically shape these seascape-scale vegetation patterns in coral reef ecosystems, influencing the occurrence of the prominent ‘halo’ pattern.

This suggests marine reserves may have even greater impacts on coral reef seascapes than previously known.

Madin explained in an article published recently in New Scientist, “The formation of the halos was driven by small fish’s fear of being eaten, so the number of predators around should be linked to whether these bare patches appear and how big they are. With fewer predators, you would expect the grazing fish to be less fearful and so venture further from the reef, resulting in wider halos.”

Using freely-available satellite, scientists came to know that there is no difference in the size of the halos inside versus outside of no-fishing marine reserves. They found that the halos are significantly more likely to occur in no-take marine reserves, demonstrating novel landscape-scale effects of marine reserves.

In the second study, scientists found that a more complex set of species interactions than previously assumed likely influence these halos. Using a combination of very high definition remote underwater video camera traps and traditional ecological studies on coral reefs within Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, Madin observed that in addition to the plant-eating fishes known to play a role in halo formation, invertebrate-eating fishes that dig in the sand for prey were disrupting the algae out to the halos’ edges and making them bigger. Another piece of the puzzle had been revealed.

Their work, in other words, suggests that the presence of halos may fill in as an indicator of aspects of reef ecosystem health because halos are associated to be the indirect outcome with healthy predator and herbivore populaces. Madin’s continuous studies of halos have demonstrated that they can show up and vanish after some time and change fundamentally in size. This phenomenon that suggests environmental factors also influence halos.

Madin said, “We urgently need more cost- and time-efficient ways of monitoring such reefs. Our work couples freely-available satellite imagery, with traditional field-based experiments and observations, to start to unravel the mystery of what the globally-widespread patterns of ‘halos’ around coral reefs can tell us about how reef ecosystems may be changing over space and/or time due to fisheries or marine reserves.”

“This will, therefore, pave the way for the development of a novel, technology-based solution to the challenge of monitoring large areas of coral reef and enable management of healthy reef ecosystems and sustainable fisheries.”