According to a new study at the Illinois Natural History Survey at the University of Illinois, the animal is most abundant in the middle part its range, a rocky expanse in southern Missouri – with up to 35,000 cubic feet of chilly Ozark river water flowing by each second.

As far as anyone can tell, the cold-water crayfish Faxonius eupunctus makes its home in a 30-mile stretch of the Eleven Point River and nowhere else in the world. Because the crayfish is so rare, environmental authorities are considering listing F. eupunctus as an endangered species. But doing so requires a thorough accounting of its population size and distribution. To achieve this, researchers used both old-school techniques and newer, high-tech methods.

Photo by Eric Larson

Research assistant Christopher Rice “The traditional way to find crayfishes in this type of river is a method called kick-seining. You take a mesh seine attached to two poles and stand out in the stream, and someone else kicks rocks and flushes water and crayfishes down into the net.”

Once caught, the animals can be counted, measured and sexed, all valuable data for those hoping to conserve them.

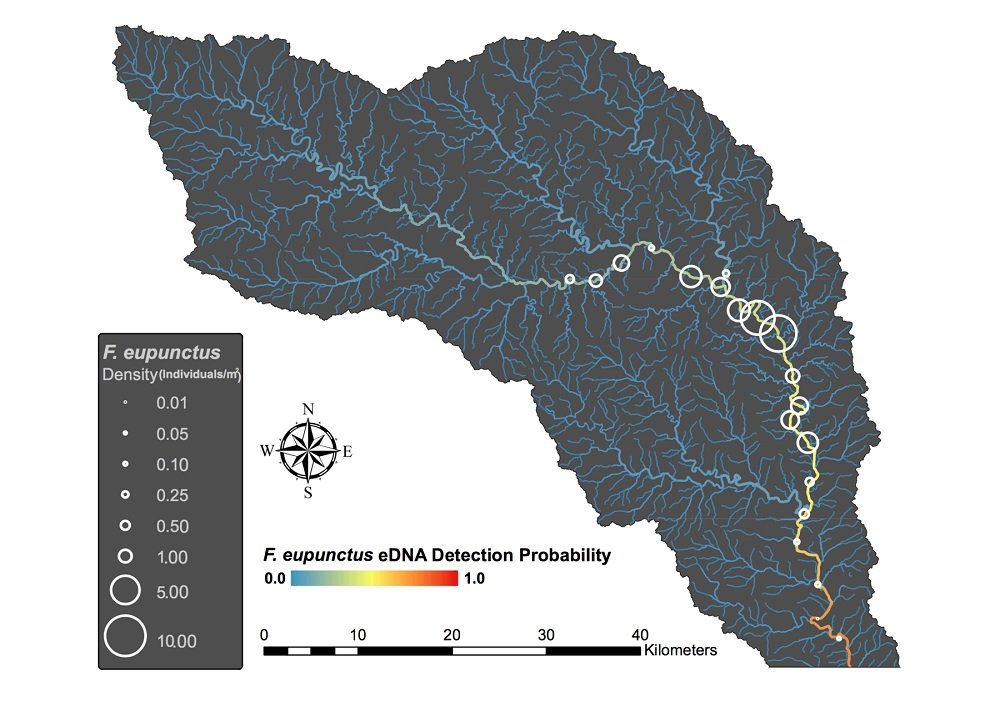

In the new study, the team kick-seined a dozen 1-square-meter plots at each of 39 sites along the river and in several smaller tributaries feeding it. That effort found F. eupunctus at 21 of 39 sites sampled. None of the crayfish were found in any of the tributaries.

Photo by Eric Larson

The researchers likewise used a technique called environmental DNA. They collected river water at each of the 39 sites, taking it back to the lab to filter and test it for F. eupunctus DNA.

Christopher Taylor, the INHS curator of fishes and crustaceans said, “One of our goals was to compare eDNA with kick-seining, to see how these methods performed in relation to one another.”

Eric Larson, a University of Illinois professor of natural resources and environmental sciences, said, scientists are still trying to work out how to use eDNA to study animals in different habitats. Using the technique in streams and rivers can be especially tricky.

Photo by Eric Larson

He added, “An animal’s DNA can degrade within hours or days in the water, depending on a lot of factors.”

Temperature, ultraviolet light and the acidity of the water can influence the rate at which it degrades.

Larson said, “This makes eDNA a very useful detection tool.”

If the DNA stuck around for years, scientists might mistakenly believe that an animal was present when it had died out years earlier. River water also moves, transporting the DNA away from where it was originally shed by the animal in the form of skin, other tissues or secretions. The team didn’t know whether eDNA would be able to detect crayfishes in the portions of the Eleven Point River where they were present.

The eDNA testing corroborated the kick-seining data, detecting F. eupunctus DNA at 19 of the 21 sites where the team had found it before. It also found no evidence of the critter in the smaller streams feeding the river.

Graphic courtesy Christopher Taylor

Taylor said, “This adds to the evidence that F. eupunctus is very rare and lives only in the Eleven Point River, providing useful information for conservationists and resource managers.”

While eDNA could fairly reliably determine whether an organism was present, it was not useful as a way of measuring abundance at specific locales, the researchers found.

Taylor added, “The ability of eDNA to work in this type of ecosystem is very exciting.”

“But our study also shows the value of doing traditional sampling. We did find the species at two locations where the eDNA did not. We also were able to directly measure abundance with the kick-seining method.”

The researchers report their findings in the journal Freshwater Biology.