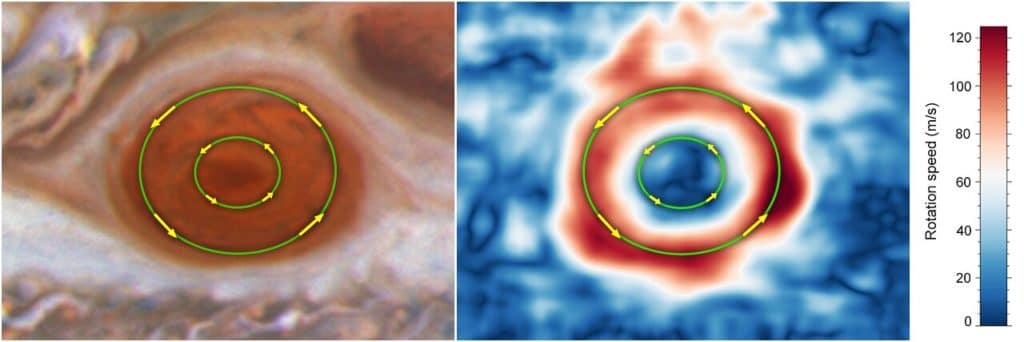

In Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a storm that has been roiling for centuries, its “outer lane” is moving faster than its “inner lane” — and continues to pick up speed. By analysing long-term data from this high-speed ring, researchers have found that the wind speed has increased by up to 8 percent between 2009 and 2020. These findings could only be made with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, which has amassed more than 10 years of regular observations, acting like a storm watcher for the planets in our Solar System.

Researchers analysing Hubble’s regular “storm reports” have found that the average wind speed just within the boundaries of the storm, known as the high-speed ring, has increased by up to 8 percent between 2009 and 2020. In contrast, the winds near the red spot’s innermost region are moving significantly more slowly.

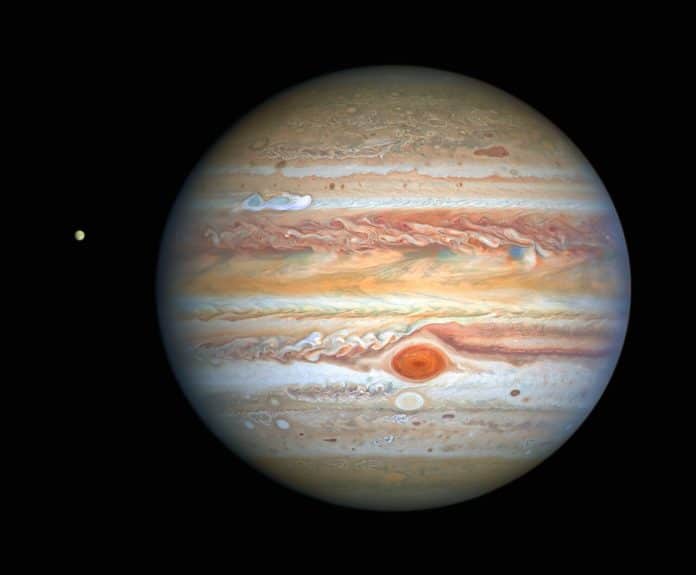

The massive storm’s coloured clouds spin counterclockwise at speeds that exceed 640 kilometres per hour — and the vortex is bigger than Earth itself. The Red Spot is legendary in part because humans have observed it for more than 150 years.

“When I initially saw the results, I asked ‘Does this make sense?’ No one has ever seen this before,” said Michael Wong of the University of California, Berkeley, who led the analysis. “But this is something only Hubble can do. Hubble’s longevity and ongoing observations make this revelation possible.”

Earth-orbiting satellites and aeroplanes track major storms on Earth closely in real time. “Since we don’t have a storm chaser plane at Jupiter, we can’t continuously measure the winds on site,” explained Amy Simon of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who contributed to the research. “Hubble is the only telescope that has the kind of temporal coverage and spatial resolution that can capture Jupiter’s winds in this much detail.”

The change in wind speed they have measured with Hubble amounts to less than 2.5 kilometres per hour per Earth year. “We’re talking about such a small change that if we didn’t have eleven years of Hubble data, we wouldn’t know it had happened,” said Simon. “With Hubble we have the precision we need to spot a trend.” Hubble’s ongoing monitoring allows researchers to revisit and analyse its data very precisely as they keep adding to it. The smallest features Hubble can reveal in the storm are a mere 170 kilometres across.

To better analyse Hubble’s bounty of data, Wong took a new approach to his data analysis. He used software to track tens to hundreds of thousands of wind vectors (directions and speeds) each time Jupiter was observed by Hubble.

What does the increase in speed mean? “That’s hard to diagnose, since Hubble can’t see the bottom of the storm very well. Anything below the cloud tops is invisible in the data,” explained Wong. “But it’s an interesting piece of the puzzle that can help us understand what’s fueling the Great Red Spot and how it’s maintaining its energy.” There’s still a lot of work to do to fully understand it.

Astronomers have pursued ongoing studies of the “king” of Solar System storms since the 1870s. The Great Red Spot is an upwelling of material from Jupiter’s interior. If seen from the side, the storm would have a tiered, wedding-cake structure with high clouds at the centre cascading down to its outer layers. Astronomers have noted that it is shrinking in size and becoming more circular than oval in observations spanning more than a century. The current diameter is 16 000 kilometres across, meaning that Earth could still fit inside it.

In addition to observing this legendary, long-lived storm, researchers have observed storms on other planets, including Neptune, where they tend to travel across the planet’s surface and disappear after only a few years. Research like this helps scientists not only learn about the individual planets, but also draw conclusions about the underlying physics that drives and maintains planets’ storms.

The majority of the data to support this research came from Hubble’s Outer Planets Atmospheres Legacy (OPAL) program, which provides annual Hubble global views of the outer planets that allow astronomers to look for changes in the planets’ storms, winds, and clouds.

Journal Reference

- Wong, M. H., Marcus, P. S., Simon, A. A., de Pater, I., Tollefson, J. W., & Asay-Davis, X. (2021). Evolution of the horizontal winds in Jupiter’s Great Red Spot from one Jovian year of HST/WFC3 maps. Geophysical Research Letters, 48, e2021GL093982. DOI: 10.1029/2021GL093982