Dogs have a good sense of smell. Through just a smell, they can identify any object, person etc. Among dogs and other animals that rely on smell, at least one factor that may give them an advantage is a sheet of tissue in the nasal cavity.

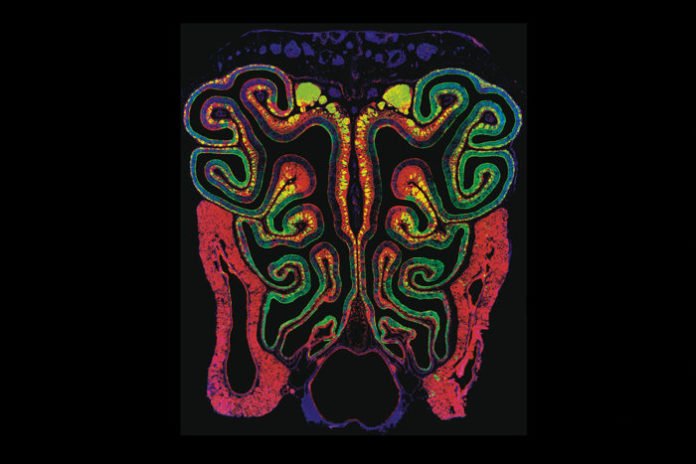

In human, the sense of smell is developed by olfactory epitheliums-a a single flat sheet lining the roof of the nasal cavity. The olfactory epithelium contains specialized neurons that bind to odor molecules and send signals to the brain that are interpreted as the smell. Dogs have hundreds of millions more of these neurons than people do.

Presently, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have revealed new subtle details in how the olfactory epithelium creates. The data could enable researchers to demonstrate that turbinates and the subsequent bigger surface area of the olfactory epithelium are one conclusive reason dog notice so well.

Scientists found that the surface area of the sheet matters in how well animals smell and in the types of smells they can detect. The cells called FEP cells here plays a vital part in controlling the size of the surface area of the olfactory epithelium.

David M. Ornitz, MD, PhD, the Alumni Endowed Professor of Developmental Biology said, “One reason we think this stems from differences in the complexity of these turbinates. Animals that we think of as having a great sense of smell have really complex turbinate systems.”

Scientists expect that the study could also help them demonstrate How did animals’ senses of smell become so enormously variable. Understanding these signals could help scientists tease out how dogs evolved an extraordinary olfactory system and humans wound up with a comparatively stunted one.

These stem cells likewise send a particular signaling molecule to the hidden turbinates, instructing them to develop. The confirmation proposes that this signaling crosstalk between the epithelium and the turbinates manages the size of the olfactory system that winds up growing, now and then bringing about olfactory epithelia with bigger surface territories, for example, in dogs.

When the stem cells can’t signal properly, turbinate growth and olfactory epithelium surface area experience an arrested development. To study this in the lab, mice with such olfactory stunting could, in theory, be compared with typical mice to learn more about how these signals govern the final complexity of an animal’s olfactory system.

Lu M. Yang, a graduate student in Ornitz’s lab said, “Before our study, we didn’t know how the epithelium expands from a tiny patch of cells to a large sheet that develops in conjunction with complex turbinates. We can use this to help understand why dogs, for example, have such a good sense of smell. They have extremely complex turbinate structures, and now we know some of the details about how those structures develop.”

The study is published in the journal Developmental Cell.