Generally, humans who lose their sense of smell because of age, injury or diseases such as Parkinson. But the cause has been unclear because of the loss of pleasure in eating.

We rely on one the sense of taste and sight when picking, eating and smelling food. During an experiment, scientists at the University of California, Berkeley found that mice who lost their sense of smell also lost weight.

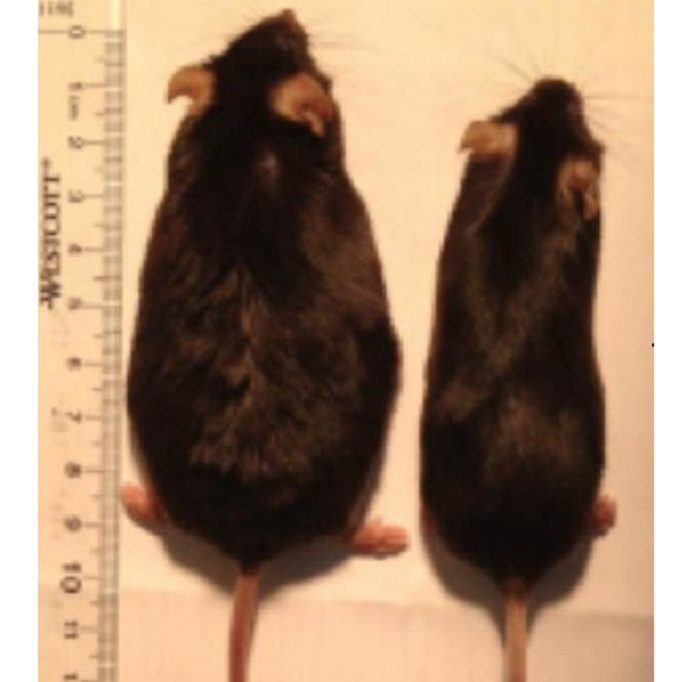

These slimmed-down but smell-deficient mice ate the same amount of fatty food as mice that retained their sense of smell and ballooned to twice their normal weight. Additionally, super smellers mice got even fatter on a high-fat diet than mice with the normal smell.

Meanwhile, smelling food that we eat mimics an important role in how the body deals with calories. If you can’t smell your food, it may burn calories instead of storing it.

The results state a connection between the olfactory or smell system and regions of the brain that regulates metabolism, in particular, the hypothalamus.

Céline Riera, a former UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow said, “This paper is one of the first studies that really show if we manipulate olfactory inputs we can actually alter how the brain perceives energy balance, and how the brain regulates energy balance.”

The study suggests that the loss of smell itself plays a role, and suggests possible interventions for those who have lost their smell.

Senior author Andrew Dillin said, “Sensory systems play a role in metabolism. Weight gain isn’t purely a measure of the calories taken in. It also related to how those calories are perceived. If we can validate this in humans, perhaps we can actually make a drug that doesn’t interfere with the smell but still blocks that metabolic circuitry. That would be amazing.”

During the experiment, scientists used gene therapy to destroy olfactory neurons in the noses of adult mice but spare stem cells. This allows them to regrow the olfactory neurons.

The smell-deficient mice rapidly burned calories by up-regulating their sympathetic nervous system. The mice turned their beige fat cells into brown fat cells, which burn fatty acids to produce heat. Some of them become lean means burning machines.

The mice also have white fat cells which are associated with poor health outcomes.

On the negative side, the loss of smell was accompanied by a large increase in levels of the hormone noradrenaline, which is a stress response tied to the sympathetic nervous system. In humans, such a sustained rise in this hormone could lead to a heart attack.

Dillin said, “It would be a drastic step to eliminate smell in humans wanting to lose weight. It might be a viable alternative for the morbidly obese contemplating stomach stapling or bariatric surgery, even with the increased noradrenaline.”

“For that small group of people, you could wipe out their smell for maybe six months and then let the olfactory neurons grow back after they’ve got their metabolic program rewired.”

With the aim of temporarily blocking the sense of smell in adult mice, scientists developed two different techniques. They genetically engineered mice to express a diphtheria receptor in their olfactory neurons, which reach from the nose’s odor receptors to the olfactory center in the brain. When diphtheria toxin was sprayed into their nose, the neurons died, rendering the mice smell-deficient until the stem cells regenerated them.

In addition, they also engineered a benign virus to carry the receptor into olfactory cells only via inhalation. This knocked out their sense of smell for about three weeks.

Scientists found that the mice ate as much of the high-fat food as did the mice that could still smell. The mice also gained at most 10 percent more weight. For the former, insulin sensitivity and response to glucose, both are disturbed in metabolic disorders like obesity.

Mice that were already obese lost weight after their smell was knocked out, slimming down to the size of normal mice while still eating a high-fat diet. These mice lost only fat weight, with no effect on muscle, organ or bone mass.

Riera said, “People with eating disorders sometimes have a hard time controlling how much food they are eating and they have a lot of cravings. We think olfactory neurons are very important for controlling pleasure of food and if we have a way to modulate this pathway, we might be able to block cravings in these people and help them with managing their food intake.”