Bile is made in the liver. It contains a mix of products such as bilirubin, cholesterol, and bile acids and salts. Bile ducts are drainage “pipes” that carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder and from the gallbladder to the small intestine.

In other words, Bile ducts act as the liver’s waste disposal system. Malfunctioning bile ducts are behind a third of adults and 70 percent of children’s liver transplantations, with no alternative treatments. There is currently a shortage of liver donors: according to the NHS, the average waiting time for a liver transplant in the UK is 135 days for adults and 73 days for children. This means that only a limited number of patients can benefit from this therapy.

Increasing organ availability or providing an alternative to whole organ transplantation could be the solution.

In a study published today in Science, scientists at the University of Cambridge have developed a new approach. Using a technique, they grow bile duct organoids – often referred to as ‘mini-organs’ in the lab to repair human livers in regenerative medicine first. Their approach could repair damaged organ donor livers so that they can still be used for transplantation.

This new approach relies on a recent ‘perfusion system’ used to maintain donated organs outside the body. Using this technology, scientists demonstrated that it is possible to transplant biliary cells grown in the lab known as cholangiocytes into damaged human livers to repair them.

Dr. Fotios Sampaziotis from the Wellcome-MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute said, “Given the chronic shortage of donor organs, it’s important to look at ways of repairing damaged organs or even provide alternatives to organ transplantation. We’ve been using organoids for several years to understand biology and disease or their regeneration capacity in small animals. Still, we have always hoped to be able to use them to repair damaged human tissue. Ours is the first study to show, in principle, that this should be possible.”

Scientists used single-cell RNA sequencing and organoid culture techniques to determine that the duct cells differentiate biliary cells from the gallbladder. The disease usually spares this and could be converted to the bile duct cells usually destroyed in condition (intrahepatic ducts) and vice versa using a bile component known as bile acid. This means that the patient’s cells from disease-spared areas could be used to repair destroyed ducts.

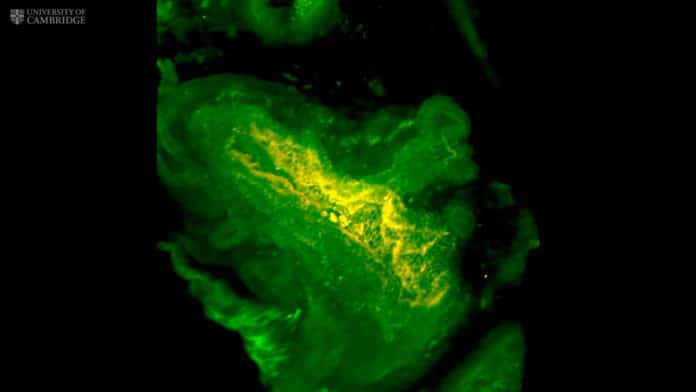

Scientists tested their hypothesis by growing gallbladder cells as organoids in the lab. After grafting these gallbladder organoids into mice, they found that the organoids were indeed able to repair damaged ducts, opening up avenues for regenerative medicine applications in the context of diseases affecting the biliary system.

The team used the technique on human donor livers taking advantage of the perfusion system used by researchers based at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, part of Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation. They injected the gallbladder organoids into the human liver and showed for the first time that the transplanted organoids repaired the organ’s ducts and restored their function. This study, therefore, confirmed that their cell-based therapy could be used to repair damaged livers.

Professor Ludovic Vallier from the Wellcome-MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute, joint senior author, said: “This is the first time that we’ve been able to show that a human liver can be enhanced or repaired using cells grown in the lab. We have further work to do to test the safety and viability of this approach, but hopefully, we will be able to transfer this into the clinic in the coming years.”

Mr. Kourosh Saeb-Parsy from the Department of Surgery at the University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, joint senior author, added: “This is an important step towards allowing us to use organs previously deemed unsuitable for transplantation. In the future, it could help reduce the pressure on the transplant waiting list.”

Journal Reference:

- Sampaziotis, F et al. Cholangiocyte organoids can repair bile ducts after transplantation in the human liver. Science; 18 Feb 2021. DOI: 10.1126/science.aaz6964