A tape recorder, an analog audio machine, uses magnetic tape for sound recording. Tape recorders can store many different forms of information. They come in a variety of sizes.

Now, scientists at the University of Columbia have developed the world’s smallest tape recorder from human gut microbe Escherichia coli. They just converted a natural bacterial immune system into a microscopic data recorder.

This smallest tape recorder uses ubiquitous human gut microbe Escherichia coli by enabling it to store information about their interactions with the environment. It also records the time-stamp events.

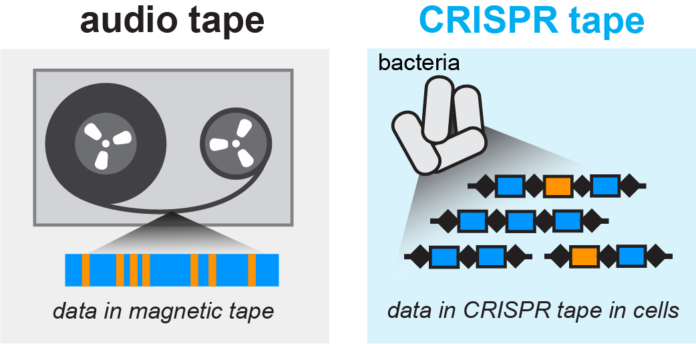

Scientists took advantage of CRISPR-Cas, an immune system in many species of bacteria. CRISPR-Cas duplicates scraps of DNA from attacking infections with the goal that consequent ages of microscopic organisms can repulse these pathogens all the more viable. Hence, the genome accumulates a chronological record of the bacterial viruses.

Harris Wang, Senior author of the study, said, “The CRISPR-Cas system is a natural biological memory device. From an engineering perspective that’s actually quite nice, because it’s already a system that has been honed through evolution to be really great at storing information.”

Generally, CRISPR-Cas uses its recorded sequences to detect and cut the DNA of incoming phages. This specification of CRISPR-Cas makes it a darling for various gene therapies. Hence, many clinical trials are underway using CRISPR-Cas gene therapies.

Ravi Sheth, a graduate student in Wang’s laboratory, observed the unrealized potential of CRISPR-Cas, i.e., its recording function.

He said, “When you think about recording temporally changing signals with electronics, or an audio recording … that’s a very powerful technology, but we were thinking how can you scale this to living cells themselves?”

To build this tape recorder, scientists modified a piece of DNA called Plasmid, by giving it the ability to create more copies of itself in the bacterial cell in response to an external signal. A separate recording Pasmids, which drives the recorder and marks time, expresses components of the CRISPR-Cas system. In the absence of an external signal, only the recording plasmids are active, and the cell adds copies of a spacer sequence to the CRISPR locus in its genome.

When an external signal is detected by the cell, the other plasmids are also activated, leading to the insertion of its sequences instead. The result is a mixture of background sequences that record time and signal sequences that change depending on the cell’s environment. The researchers can then examine the bacterial CRISPR locus and use computational tools to read the recording and its timing.

Dr. Wang said, “Now we’re planning to look at various markers that might be altered under changes in natural or disease states, in the gastrointestinal system or elsewhere.”

Journal Reference

- Ravi U. Sheth et al. , Multiplex recording of cellular events over time on CRISPR biological tape. Science 358, 1457-1461 (2017). DOI: 10.1126/science.aao0958