Bose-Einstein condensates are sometimes described as the fifth state of matter. They were only created in a lab as recently as 1995. They experience the same quantum state—almost like coherent photons in a laser—and start to clump together, occupying the same volume as one indistinguishable super atom.

Currently, BECs remain the subject of much basic research for simulating condensed matter systems, but in principle, they have applications in quantum information processing. Most BECs are fabricated from dilute gases of ordinary atoms. But until now, a BEC made out of exotic atoms has never been achieved.

Scientists from the University of Tokyo wanted to see if they could make a BEC out of excitons. Using quasiparticles, they have created the first Bose-Einstein condensate — the mysterious “fifth state” of matter. The finding is set to significantly impact the development of quantum technologies, including quantum computing.

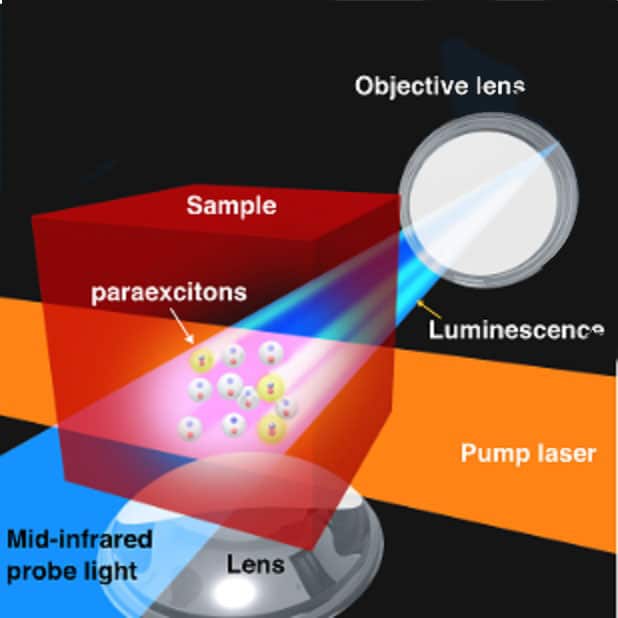

Combined electron-hole pair is an electrically neutral “quasiparticle” called an exciton. The exciton quasiparticle can also be described as an exotic atom because it is, in effect, a hydrogen atom that has had its single positive proton replaced by a single positive hole.

Makoto Kuwata-Gonokami, a physicist at the University of Tokyo and co-author of the paper, said, “Direct observation of an exciton condensate in a three-dimensional semiconductor has been highly sought after since it was first theoretically proposed in 1962. Nobody knew whether quasiparticles could undergo Bose-Einstein condensation in the same way as real particles. It’s kind of the holy grail of low-temperature physics.”

Because of their extended lifetime, the paraexcitons produced in cuprous oxide (Cu2O), a mixture of copper and oxygen, were regarded to be one of the most promising possibilities for generating exciton BECs in a bulk semiconductor. In the 1990s, attempts to produce paraexciton BEC at liquid helium temperatures of about 2 K had been made. Still, they had failed because far lower temperatures are required to produce a BEC out of excitons. Because they are too transient, orthoexcitons cannot attain such a low temperature. However, it is known from experiments that paraexcitons have a very long lifetime of over a few hundred nanoseconds, which is sufficient to cool them to the necessary temperature of a BEC.

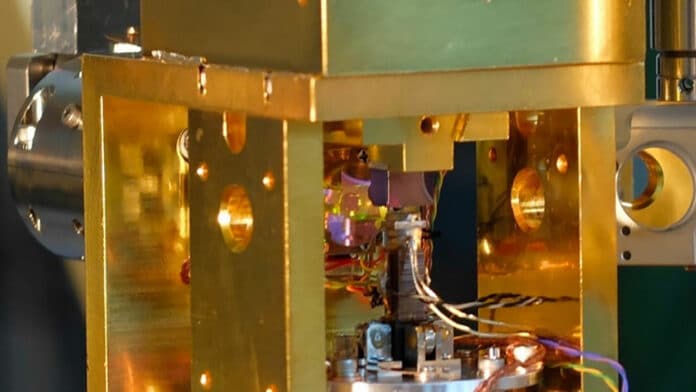

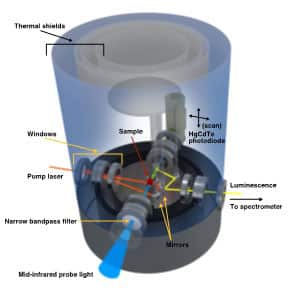

The team employed a dilution refrigerator, a cryogenic apparatus that cools by combining two isotopes of helium and is frequently used by scientists trying to develop quantum computers, to trap paraexcitons in the majority of Cu2O below 400 millikelvins. Then, they used mid-infrared induced absorption imaging, a sort of microscopy that uses light in the middle of the infrared range, to directly view the exciton BEC in actual space.

As a result, the team could obtain precise measurements of the exciton density and temperature, which allowed them to identify differences and similarities between exciton BEC and conventional atomic BEC.

Scientists further want to investigate the dynamics of how the exciton BEC forms in the bulk semiconductor and to investigate collective excitations of exciton BECs. Their ultimate goal is to build a platform based on a system of exciton BECs to further elucidate its quantum properties and to develop a better understanding of the quantum mechanics of qubits that are strongly coupled to their environment.

Journal Reference:

- Yusuke Morita, Kosuke Yoshioka, and Makoto Kuwata-Gonokami, “Observation of Bose-Einstein condensates of excitons in a bulk semiconductor,” Nature Communications: September 14, 2022. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-33103-4