According to an estimate, almost 600 million of people contract listeriosis each year. And the rate of death among them in the value is average 420,000. Pregnant women, newborn children, adults 65 and older and people with weakened immune systems are most at risk. The pathogen is found most often in deli meat, hot dogs, dairy products and produce.

Scientists at the Purdue University have discovered another way that Listeria uses to enter the circulatory system, proposing that types of the foodborne microscopic organisms considered favorable might be more unsafe than once thought.

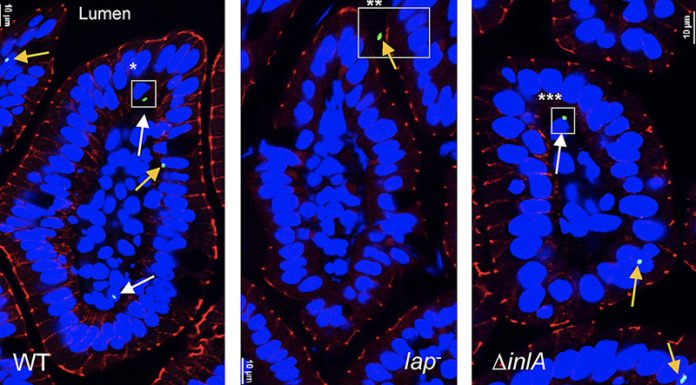

To contaminate somebody, the Listeria monocytogenes microorganisms must cross the epithelial boundary, a mass of cells in the gut that for the most part shields the circulatory system from unsafe pathogens. It has for some time been trusted that a protein called Internalin A, found in numerous types of Listeria, is required for getting through that boundary.

Arun Bhunia, a Purdue food microbiology professor in the Department of Food Science said, “We fed Listeria to mice that have a non-functional receptor for the Internalin A protein. If Internalin A is required for Listeria monocytogenes bacteria to reach the bloodstream, these mice should not have been infected. But they were.”

“As soon as we feed the mice this bacterium, it goes through the intestine and crosses this epithelial barrier and into the blood circulation, liver and spleen. This suggests there is another way in which Listeria monocytogenes gets through these cells and into the bloodstream.”

The study shows that Listeria attachment protein (LAP) associates with warm stun protein (HSP) in mice, at that point the epithelial cells move separated to give the bacterium access to the circulatory system. Be that as it may, that is only one way the microbes may use to taint a host. Since the Internalin A receptors are sandwiched between epithelial cells in people, they are out of reach to the Internalin A protein.

Listeria strains that have the defective or nonfunctional Internalin A protein haven’t been considered dangerous. But if the bacteria have another way through the gut and into the bloodstream regardless of Internalin A, that’s no longer true.

Bhunia said, “When LAP interacts with HSP, those cells move apart, not only giving the bacterium access to the bloodstream but also exposing the Internalin A receptors and allowing transport of Listeria monocytogenes into the bloodstream, which likely happens in humans. Now that we know the mechanism, we can look at how to block this pathway to prevent the infection.”

Rishi Drolia, a graduate research assistant in Bhunia’s lab said, “We cannot just think that because most of these bacteria that are found in food are Internalin A mutants, we can tolerate it. We can still get infected.”

Now, scientists are working to further develop a vaccine that blocks LAP, which could be a method for keeping Listeria from reaching the bloodstream. Bhunia’s findings reported in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.