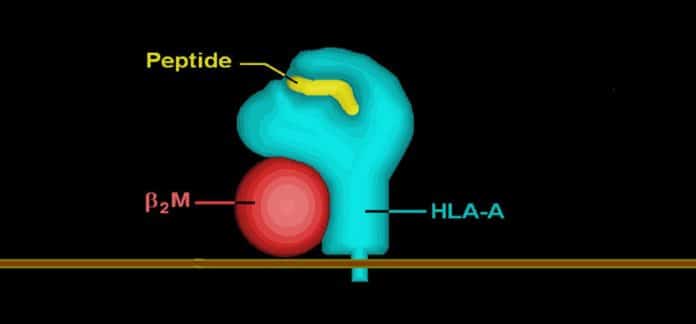

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system (the major histocompatibility complex [MHC] in humans) is an essential part of the immune system. These genes produce HLA molecules that are situated on the outside of cells.

When a virus infects an organism, the invader’s proteins are first to cut into little sections called peptides. The HLA molecules at that point tie on to these fragments and open them to the outside of the phones, accordingly setting off a course of immunity reactions intended to dispense with the virus.

From the 450 or so most common HLA molecules in hundreds of populations worldwide, scientists in a new study tried to identify the ones that are most strongly bound to the peptides of the new coronavirus. Over 7,000 peptides can be derived from all of the viral proteins of the coronavirus.

Scientists used bioinformatic tools to perform the analysis. These can predict the binding affinities between the HLA molecules and the viral peptides based on their physical and chemical properties. The scientists then turned to statistical models to compare the frequencies of these HLA variants in different human populations.

Scientists classified almost 450 HLA molecules according to their relative capacity to bind the coronavirus peptides. It gives a fundamental reference inventory to recognizing the genetic resistance or susceptibility of individuals to the virus. The investigation has likewise demonstrated that the frequencies of these HLA variations differ altogether, starting with one populace then onto the next.

José Manuel Nunes, a researcher at the Anthropology Unit – and co-author of the article – further explains: “We were surprised to find that Indigenous populations in America had both the highest frequencies of HLA variants that bind the most strongly to the peptides and the lowest frequencies of those that bind the least strongly.”

“HLA molecules contribute to the immune response, but they are far from being the only element that can be used to predict effective or ineffective resistance to a virus. This is also verified on the ground since America’s Indigenous populations are apparently no less affected than others by COVID-19.”

Scientists also analyzed the HLA-peptide bindings for all of the proteins of the six other viruses with pandemic potential (two other coronaviruses, three influenza viruses, and the HIV-1 virus of AIDS). This showed that many HLA variants are capable of binding firmly to the peptides of all seven viruses studied. Others do the same for all respiratory-type viruses (coronavirus and influenza). This means that numerous “generalist” HLA molecules are effective against several different viruses.

Professor Sanchez-Mazas said, “The differences between populations observed in this study are differences in the frequencies of the generalist HLA variants that do not bind specifically to the coronavirus but also other pathogens. This is what makes us think that the current differences between populations are the result of past adaptations to different pathogenic pressures, which is extremely informative for understanding the genetic evolution of our species.”

A logical follow-up to the study will be to determine precisely which coronavirus peptides are most strongly bound to the HLA molecules. It is these peptides that will have the highest chances of triggering an effective immune reaction. Identifying them will be vital for developing a vaccine.

Journal Reference:

- Rodrigo Barquera et al., Binding affinities of 438 HLA proteins to complete proteomes of seven pandemic viruses and distributions of strongest and weakest HLA peptide binders in populations worldwide. DOI: 10.1111/tan.13956