Myoblast fusion is tightly regulated during development and regeneration of muscle fibers. BAI3 is a receptor that orchestrates myoblast fusion via Elmo/Dock1 signaling, but the mechanisms regulating its activity remain elusive.

In a new study by the University of Montreal, scientists discovered two proteins fundamental to the improvement of skeletal muscle. The study could prompt a superior comprehension of rare muscular diseases and the advancement of new medications.

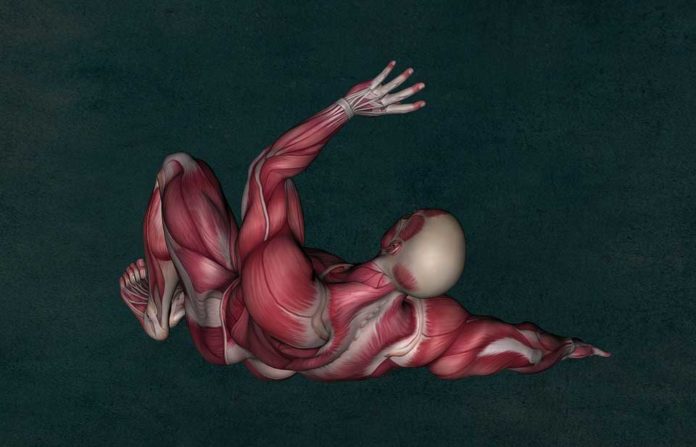

Skeletal muscles are attached to our bones and enable our bodies to move. Whether in a developing embryo or a professional athlete, the same sequence leads to their formation.

Lead author Jean-François Côté said, “In vertebrates, cells derived from stem cells, called myoblasts, first align with each other and come so close as to eventually touch and compress their cell membranes.”

“Ultimately, myoblasts merge to create one large cell. This phenomenon, called “cell fusion”, is very particular. Cell fusion involves just a few tissues, including the development of the placenta and the remodeling of our bones.”

In order to develop or repair the muscle, myoblasts need to function properly. No false move is permissible, otherwise, there will be defects. During the study, scientists discovered two proteins – ClqL4 and Stabilin-2 – that regulate this singular choreography.

ClqL4 and Stabilin-2 guarantee fruitful fulfillment of this delicate succession. They back off and trigger cell combination separately at key minutes. Their role is significant: if the “metronome” of myoblasts is interfered with, the muscles won’t be the correct size, and their capacity will be influenced. This is the thing that occurs in muscle diseases portrayed by a shortcoming that makes certain developments troublesome.

Côté said, “The discovery of the proteins is the culmination of an international collaboration between teams from Montreal, Japan, the United States, and South Korea. Our second author, Viviane Tran, one of my doctoral students, spent time in Tokyo to conduct important experiments in the lab of Michisuke Yuzaki.”

Now, scientists want to further determine whether the results of their research could become a therapeutic target for rare muscle diseases such as myopathies and muscular dystrophies.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.