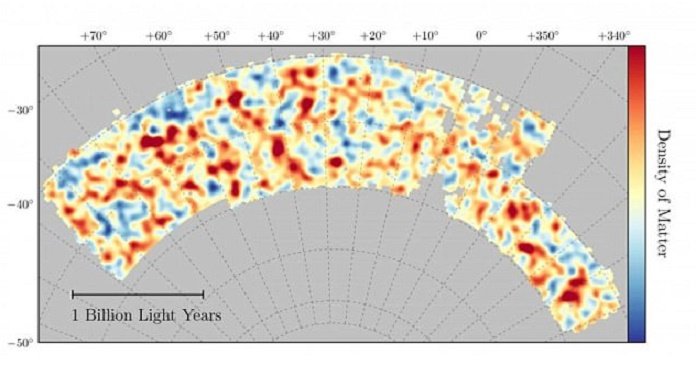

As a part of the ongoing Dark Energy Survey (DES), a study of distant galaxies allowed researchers to draw the most detailed map of the universe’s dark matter. By measuring the light emitted from 26 million galaxies, scientists drew a 10 times bigger map than the last one.

According to the researchers, it could help us understand how the universe has evolved over 14 billion years.

Since 2013, the universal group behind the DES has been doing a profound wide-area scan of about 1/8th of the night sky. They just want to collect data on some 300 million galaxies and billions of light-years from Earth to discover what this dark energy business is all about.

There is a large difference between the dark energy and dark matter. But both are tightly bound by their nature.

Dark energy is something like a black box that clarifies why the Universe is quickening in its development.

On the other hand, dark matter is more about pulling stuff than pushing space apart. Just as mysterious, it’s a black box that explains why galaxies hold together despite not seeming to have enough visible matter.

Understanding how the Universe spreads out over time and how its matter clumps together could reveal more about what exactly these things are. This requires realizing what everything looked like around 14 billion years prior when the Universe still had its infant smooth skin, an accomplishment that requires a camera that can think back in time.

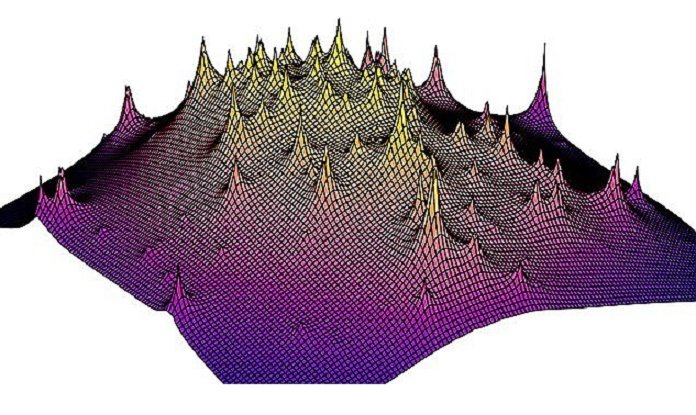

By using the Planck telescope, scientists captured a snapshot in the form of the Cosmic Microwave Background. That was a map of the radiation still humming through the Universe as an echo of its earliest days.

In 2015, scientists provided the first cosmos map based on data from 2 million galaxies collected by its Dark Energy Camera. A new map scientists generate is 10 times bigger using gravitational lensing.

Comparing Planck’s map with the one produced by the DES supports the consensus on how much dark matter and dark energy there seems to be.

Researcher Joe Zuntz from the University of Edinburgh said, “The DES measurements when compared with the Planck map, support the simplest version of the dark matter/dark energy theory. The moment we realized that our measurement matched the Planck result within 7 percent was thrilling for the entire collaboration.”

The difference between the two results could mean that mass is clumping more slowly than current physics predicts. It indirectly indicates something undiscovered.

Professor Scott Dodelson said, “This result is beyond exciting. For the first time, we’re able to see the current structure of the universe’s dark matter with the same clarity that we can see its infancy. We can follow the threads from one to the other, confirming many predictions along the way.”