Marine heat waves (MHW) can drastically impact the overall health of marine ecosystems around the globe. There has been a considerable effort to characterize the timing, intensity, duration, and physical drivers of both individual and composite MHW events.

However, MHW research has primarily focused on the surface signature of these events. The “The Blob” marine heat wave, which occurred between 2013 and 2016, warmed a significant area of surface waters in the northern Pacific, upsetting marine ecosystems around the West Coast, lowering salmon returns, and harming commercial fisheries. Also, it sparked a flurry of studies on the dramatic warming of ocean surface waters.

A new study by NOAA shows that while surface MHWs (SMHW) can dramatically impact marine ecosystems, marine heat waves also happen deep underwater. Extreme warming along the seafloor can also have significant biological outcomes.

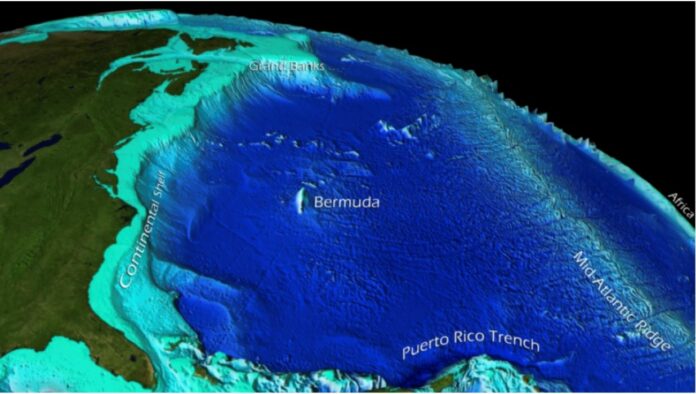

Using a combination of observations and computer models, scientists generated the first broad assessment of bottom marine heat waves in the productive continental shelf waters surrounding North America. This is the first time scientists have been able to dive deeper and assess how these extreme events unfold along shallow seafloors.

The scientists conducted the assessment using a data product known as “reanalysis,” which starts with available observations. It uses computer models to simulate ocean currents and the impact of the atmosphere to fill in the blanks. Scientists at NOAA have used a similar method to reconstruct global weather going back to the early 19th century.

The team found that on the continental shelves around North America, bottom marine heat waves tend to persist longer than their surface counterparts. Moreover, they can have more significant warming signals than the overlying surface waters.

Lead author Dillon Amaya, a research scientist with NOAA’s Physical Science Laboratory, said, “But bottom marine heat waves can also occur with little or no evidence of warming at the surface, which has important implications for the management of commercially important fisheries. That means it can be happening without managers realizing it until the impacts start to show.”

Additionally, abnormally warm bottom water temperatures have been linked to changes in the survival rates of young Atlantic cod, the spread of invasive lionfish along the southeast coast of the United States, coral bleaching and subsequent declines in reef fish, and the disappearance of near-shore lobster populations in southern New England.

Scientists noted, “It will be important to maintain existing continental shelf monitoring systems and to develop new real-time monitoring capabilities to alert marine resource managers to bottom warming conditions.”

Co-author Michael Jacox, a research oceanographer who splits his time between NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center and the Physical Sciences Laboratory, said, “We know that early recognition of marine heat waves is needed for proactive management of the coastal ocean. Now it’s clear that we need to pay closer attention to the ocean bottom, where some of the most valuable species live and can experience heat waves quite different from those on the surface.”

Journal Reference:

- Amaya, D.J., Jacox, M.G., Alexander, M.A. et al. Bottom marine heatwaves along the continental shelves of North America. Nat Commun 14, 1038 (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-36567-0