A new study by the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has discovered that immune cells surrounding the brain produce a molecule that is then absorbed by neurons in the brain. The molecule IL-17, produced by immune cells residing in areas around the brain, affects brain function through interactions with neurons to influence anxiety-like behaviors in mice.

According to scientists, the immune system elements affect both mind and body, and the immune molecule IL-17 may be a critical link between the two.

Senior author Jonathan Kipnis, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor of Pathology and Immunology and a professor of neurosurgery, of neurology, and neuroscience, said, “We are now looking into whether too much or too little of IL-17 could be linked to anxiety in people.”

IL-17 is a cytokine, a signaling molecule that orchestrates the immune response to infection by actuating and directing immune cells.

However, how IL-17 influences brain disorders remains a mystery.

The tissues surrounding the brain team up with immune cells. Some of the cells, among them known as gamma delta T cells, produce IL-17.

In this study, scientists aimed to determine that gamma-delta T cells near the brain impact behavior.

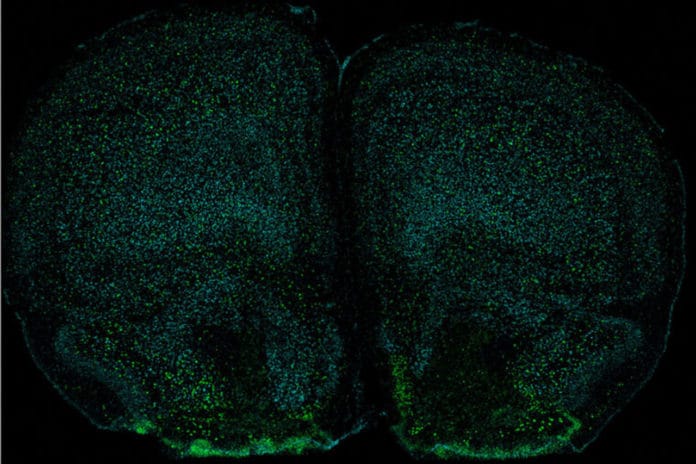

For the study, scientists used the mice model. They found that gamma-delta T cells enriched meninges continuously produce IL-17, filling the tissues surrounding the brain with IL-17.

Next, scientists put mice through established tests of memory, social behavior, foraging, and anxiety to test if gamma-delta T cells or IL-17 affect behavior.

Mice that lacked gamma-delta T cells or IL-17 were indistinguishable from mice with normal immune systems on all measures but anxiety. In the wild, open fields leave mice exposed to predators such as owls and hawks, so they’ve evolved a fear of open spaces.

Scientists conducted two separate tests that involved giving mice the option of entering exposed areas. While the mice with normal amounts of gamma-delta T cells and levels of IL-17 kept themselves mostly to the more protective edges and enclosed areas during the tests, mice without gamma-delta T cells or IL-17 ventured into the open areas, a lapse of vigilance that the researchers interpreted as decreased anxiety.

Scientists additionally found that neurons in the brain have receptors on their surfaces that respond to IL-17. When the scientists eliminated those receptors so the neurons couldn’t identify the presence of IL-17, the mice indicated less vigilance. The scientists state the discoveries recommend that behavioral changes are not a side-effect but rather an essential part of neuro-immune communication.

Although the researchers did not expose mice to bacteria or viruses to directly study the effects of infection, they injected the animals with lipopolysaccharide. This bacterial product elicits a strong immune response. Gamma-delta T cells in the tissues around the mice’s brains produced more IL-17 responses to the injection.

However, when the animals were treated with antibiotics, the amount of IL-17 was reduced, suggesting gamma-delta T cells could sense the presence of normal bacteria, such as those that make up the gut microbiome and invade bacterial species and respond appropriately to regulate behavior.

Scientists speculate that the link between the immune system and the brain could have evolved as part of a multipronged survival strategy. Increased alertness and vigilance could help rodents survive infection by discouraging behaviors that increase the risk of further infection or predation while in a weakened state.

Alves de Lima said, “The immune system and the brain have most likely co-evolved. Selecting special molecules to protect us immunologically and behaviorally at the same time is a smart way to protect against infection. This is a good example of how cytokines, which evolved to fight against pathogens, also are acting on the brain and modulating behavior.”

Scientists are now studying how gamma-delta T cells in the meninges detect bacterial signals from other parts of the body. They also are investigating how IL-17 signaling in neurons translates into behavioral changes.

Journal Reference:

- Alves de Lima K, Rustenhoven J, De Mesquita S, Wall M, Salvador AF, Smirnov I, Martelossi GC, Mamuladze T, Baker W, Papadopoulos Z, Lopes MB, Cao WS, Xie XS, Herz J, Kipnis J. Meningeal γδ T cells regulate anxiety-like behavior via IL-17a signaling in neurons. Nature Immunology. Sept. 14, 2020. DOI: 10.1038/s41590-020-0776-4