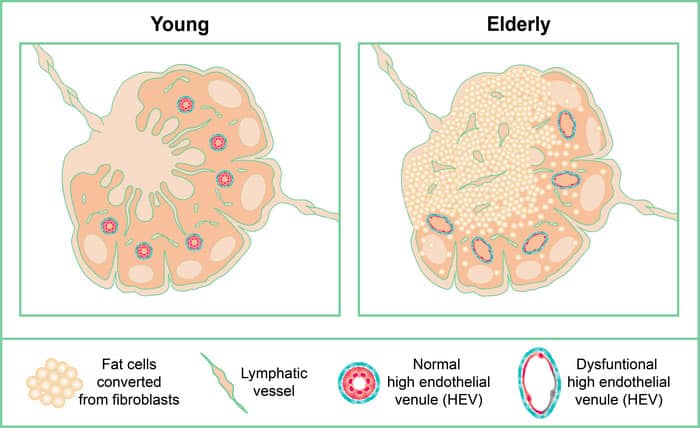

Lymph nodes normally serve as the headquarters of our immune system. A widespread but little-discussed aging-related condition called lymph node (LN) lipomatosis sees the gradual conversion of LN parenchyma into adipose tissue (fat). Unknown processes underlie these changes and their impact on the LN.

Although lipomatosis is very common and increases with age, scientists have previously devoted little discussion and research to it. Scientists at Uppsala University have just published a study that offers significant insights into the causes of human lymph node function decline with aging and the effects on immune system performance.

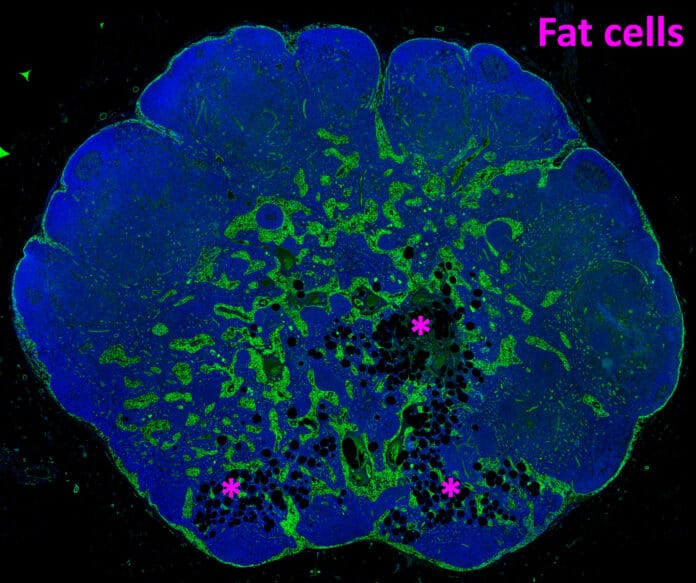

Scientists carefully examined more than 200 lymph nodes to show that lipomatosis starts in the medulla, which is the center of the lymph node. They also provided evidence connecting lipomatosis to converting lymph node supporting cells (fibroblasts) into adipocytes (fat cells). They also demonstrate that fibroblast subtypes in the medulla are more likely to develop into adipocytes.

The study demonstrates that adverse alterations occur even in the early stages of lipomatosis, reducing the lymph node’s capacity to deliver efficient immunity. Among other things, scientists see that in the regions of the lymph node where fat has grown, the specialized blood and lymphatic vessels that typically offer pathways for immune cells to enter and depart the lymph node are eliminated. Therefore, one key factor contributing to the worse response to vaccinations in elderly persons may be lipomatosis of the lymph nodes, even in its early stages. In the end, the fat dominates the lymph node and ceases to function.

Uppsala Biobank samples make up most of the study’s main source of material for analysis. Advanced image analysis has been used to analyze these samples. Additionally, the study includes research and experiments using primary stromal cell-derived cell cultures and bioinformatic analysis of gene expressions (RNA level) from two single-cell RNA sequencing (RNAseq) data sets, mouse and human. These data sets had previously been published by others but were now being examined in this study to find answers to new, more focused questions.

Tove Bekkhus, the study’s first author, said, “Our study is a first step towards understanding why lipomatosis occur and towards the longer-term goal of finding ways to prevent its progression and the destruction of the lymph node.”

Scientists are currently unable to mimic the effects they observe in human lymph nodes in animal models that are often used to study the effects of aging. This underlines the importance of studies based on direct analysis of the changes associated with aging in human subjects.

Maria H. Ulvmar, a researcher at Uppsala University who led the study, said, “I hope our work will spur interest among other researchers in including lymph nodes lipomatosis as a factor when studying elderly people’s responses to vaccination and infections. The changes we observe are also highly relevant to cancer research since the lymph nodes are the first place cancer cells spread to in several types of cancer.”

“Our publication provides the first chapter of a story about fat and loss of function in our lymph nodes when we age. We will continue developing this story by designing new studies to learn more about the underlying causes and consequences of these changes.”

Journal Reference:

- Tove Bekkhus, Anna Olofsson et al. Stromal transdifferentiation drives lipomatosis and induces extensive vascular remodeling in the aging human lymph node. The Journal of Pathology. DOI: 10.1002/path.6030