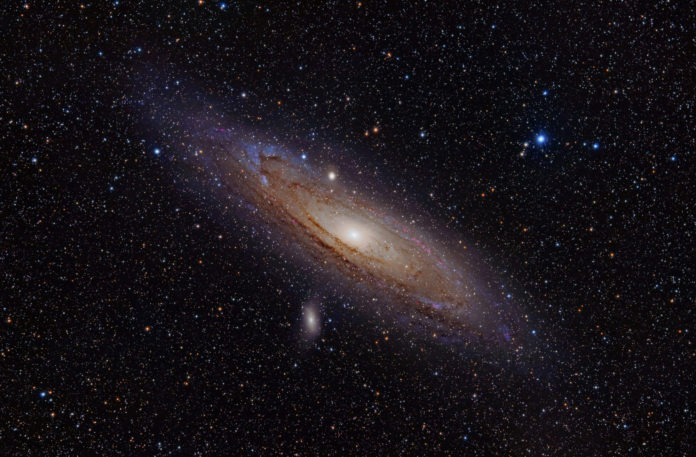

The Andromeda galaxy is the closest giant galaxy to our Milky Way. At 2.5 million light-years, it’s the most distant thing you can see with the eye alone.

In a new study, scientists mapped the big gas envelope, called a halo, surrounding the Andromeda galaxy using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. These findings surprised scientists a little bit, showing his tenuous, nearly invisible halo of diffuse plasma extends 1.3 million light-years from the galaxy—about halfway to our Milky Way—and as far as 2 million light-years in some directions.

The discovery suggests that Andromeda’s halo is already bumping into the halo of our galaxy. Along with that, the study reveals that the halo has a layered structure- containing two main nested and distinct shells of gas.

Study leader Nicolas Lehner of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana said, “We find the inner shell that extends to about a half-million light-years is far more complex and dynamic. The outer shell is smoother and hotter. This difference is a likely result from the impact of supernova activity in the galaxy’s disk more directly affecting the inner halo.”

Scientists discovered this activity’s signature- they found a large number of heavy elements in the gaseous halo of Andromeda.

Through a program called Project AMIGA (Absorption Map of Ionized Gas in Andromeda), the study analyzed the light from 43 quasars- located far beyond Andromeda. The quasars are dispersed behind the halo, permitting scientists to explore multiple regions.

Glancing through the halo at the quasars’ light, the group saw how the Andromeda halo absorbs this light and how that absorption changes in different regions. The immense Andromeda halo is made of rarified and ionized gas that doesn’t emit easily detectable radiation. Thusly, tracing the absorption of light coming from a background source is a superior method to probe this material.

Using the unique capability of Hubble’s Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS), scientists studied to study the ultraviolet light from the quasars. The COS helped scientists detecting ionized gas from carbon, silicon, and oxygen.

This is not the first time that the Andromeda halo has been probed. In 2015, scientists probing Andromeda’s halo discovered that the Andromeda halo is large and massive. But there was little hint of its complexity; now, it’s mapped out in more detail, leading to its size and mass being far more accurately determined.

Co-investigator J. Christopher Howk, also of Notre Dame, said, “Previously, there was very little information—only six quasars—within 1 million light-years of the galaxy. This new program provides much more information on this inner region of Andromeda’s halo. Probing gas within this radius is important, as it represents something of a gravitational sphere of influence for Andromeda.”

Scientists have studied gaseous halos of more distant galaxies. Still, those galaxies are much smaller on the sky, meaning the number of bright enough background quasars to probe their halo is usually only one per galaxy. Spatial information is, therefore, essentially lost. With its proximity to Earth, the gaseous halo of Andromeda looms large on the sky, allowing for a far more extensive sampling.

Lehner said, “This is truly a unique experiment because only with Andromeda do we have information on its halo along not only one or two sightlines, but over 40.”

“This is groundbreaking for capturing the complexity of a galaxy halo beyond our own Milky Way.”

Journal Reference:

- Nicolas Lehner et al. Project AMIGA: The Circumgalactic Medium of Andromeda, The Astrophysical Journal (2020). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/aba49c