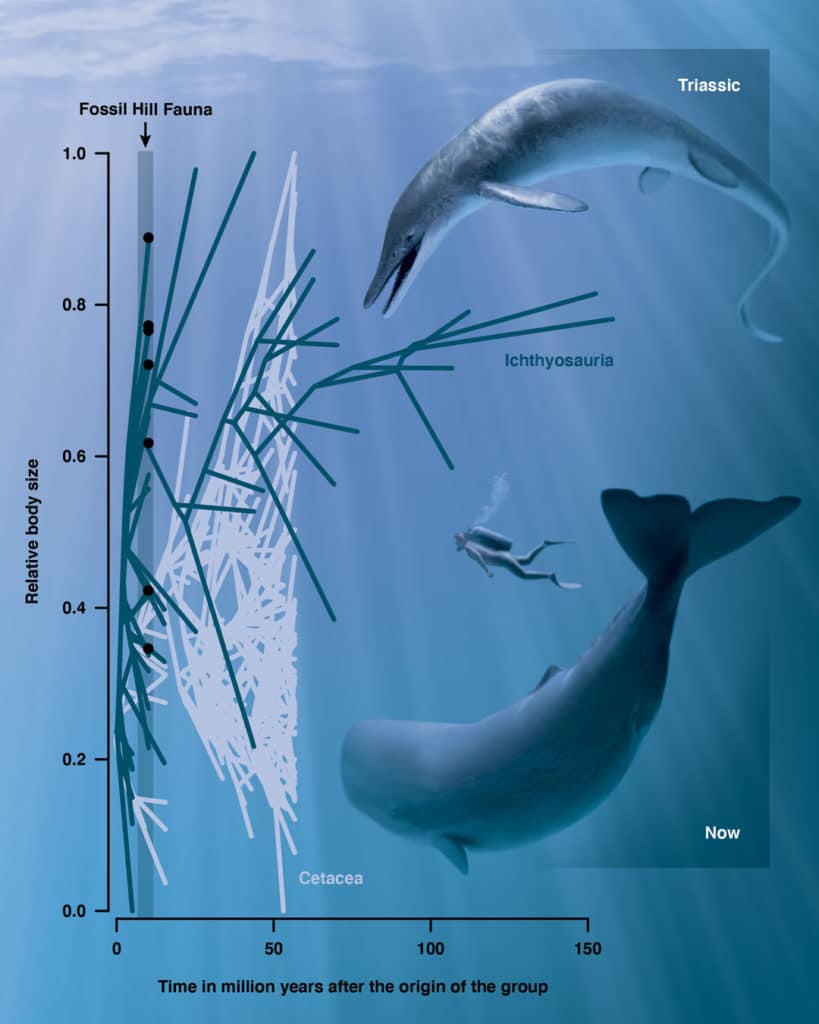

The largest animals to have ever lived occupied the marine environment. Modern cetaceans (whales and dolphins) evolved their large size over tens of millions of years in response to the increased productivity of cold marine waters. However, whales were not the first marine giants to evolve.

The two-meter skull of a newly discovered species of giant ichthyosaur, the earliest known, sheds new light on the marine reptiles’ rapid growth into behemoths of the Dinosaurian oceans and helps us better understand the journey of modern cetaceans to becoming the largest animals ever to inhabit the Earth.

The researchers published their findings in Science.

Like dinosaurs ruled the land, ichthyosaurs and other aquatic reptiles (emphatically not dinosaurs) ruled the waves.

Evolving fins and hydrodynamic body-shapes seen in both fish and whales, ichthyosaurs swam the ancient oceans for nearly the entirety of the Age of Dinosaurs.

“Ichthyosaurs derive from an as yet unknown group of land-living reptiles and were air-breathing themselves,” says lead author Dr. Martin Sander, a paleontologist at the University of Bonn and Research Associate with the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “From the first skeleton discoveries in southern England and Germany over 250 years ago, these ‘fish-saurians’ were among the first large fossil reptiles known to Science, long before the dinosaurs, and they have captured the popular imagination ever since.”

An adequately preserved skull and part of the backbone, shoulder, and forefin were excavated from a rock unit called the Fossil Hill Member in the Augusta Mountains of Nevada. It dates back to the Middle Triassic (247.2-237 million years ago). It also represents the earliest case of an ichthyosaur reaching epic proportions.

The newly named Cymbospondylus youngorum is the largest animal yet discovered from that period, on land or in the sea. It is as big as a giant sperm whale at more than 17 meters (55.78 feet) long.

“The importance of the find was not immediately apparent,” notes Dr. Sander, “because only a few vertebrae were exposed on the side of the canyon. However, the anatomy of the vertebrae suggested that the front end of the animal might still be hidden in the rocks. Then, one cold September day in 2011, the crew needed a warm-up and tested this suggestion by excavation, finding the skull, forelimbs, and chest region.”

In other mountain ranges of Nevada, paleontologists have been recovering fossils from the Fossil Hill Member’s limestone, shale, and siltstone since 1902, opening a window into the Triassic.

The mountains connect our present to ancient oceans and have produced many species of ammonites, shelled ancestors of modern cephalopods like cuttlefish and octopuses, as well as marine reptiles. These animal specimens are collectively known as the Fossil Hill Fauna, representing many C. youngorum’s prey and competitors.

C. youngorum stalked the oceans some 246 million years ago, or only about three million years after the first ichthyosaurs got their fins wet, an amazingly short time to get this big. The elongated snout and conical teeth suggest that C. youngorum preyed on squid and fish, but its size meant that it could have hunted smaller and juvenile marine reptiles as well.

The giant predator probably had some hefty competition. Through sophisticated computational modeling, the authors examined the likely energy running through the Fossil Hill Fauna’s food web, recreating the ancient environment through data, finding that marine food webs were able to support a few more colossal meat-eating ichthyosaurs. Ichthyosaurs of different sizes and survival strategies proliferated, comparable to modern cetaceans’— from relatively small dolphins to massive filter-feeding baleen whales and giant squid-hunting sperm whales.

Co-author and ecological modeler, Dr. Eva Maria Griebeler from the University of Mainz in Germany, notes, “due to their large size and resulting energy demands, the densities of the largest ichthyosaurs from the Fossil Hill Fauna including C. youngourum must have been substantially lower than suggested by our field census. The ecological functioning of this food web from ecological modeling was very exciting as modern, highly productive primary producers were absent in Mesozoic food webs and were an important driver in the size evolution of whales.”

“One rather unique aspect of this project is the integrative nature of our approach. We first had to describe the anatomy of the giant skull in detail and determine how this animal is related to other ichthyosaurs,” says senior author Dr. Lars Schmitz, Associate Professor of Biology at Scripps College and Dinosaur Institute Research Associate. “We did not stop there, as we wanted to understand the significance of the new discovery in the context of the large-scale evolutionary pattern of ichthyosaur and whale body sizes, and how the fossil ecosystem of the Fossil Hill Fauna may have functioned. Both the evolutionary and ecological analyses required a substantial amount of computation, ultimately leading to a confluence of modeling with traditional paleontology.”

They found that while cetaceans and ichthyosaurs evolved very large body sizes, their respective evolutionary trajectories toward gigantism differed. Ichthyosaurs had an initial boom in size, becoming giants early on in their evolutionary history, while whales took much longer to reach the outer limits of huge. They found a connection between large size and raptorial hunting—think of a sperm whale diving down to hunt giant squid—and a link between large size and a loss of teeth—think of the giant filter-feeding whales that are the largest animals ever to live on Earth.

“As researchers, we often talk about similarities between ichthyosaurs and cetaceans, but rarely dive into the details. That’s one way this study stands out, as it allowed us to explore and gain some additional insight into body size evolution within these groups of marine tetrapods,” says NHM’s Associate Curator of Mammalogy (Marine Mammals), Dr. Jorge Velez-Juarbe. “Another interesting aspect is that Cymbospondylus youngorum and the rest of the Fossil Hill Fauna are a testament to the resilience of life in the oceans after the worst mass extinction in Earth’s history. You can say this is the first big splash for tetrapods in the oceans.”

Journal Reference

- P. Martin Sander, Eva Maria Griebeler, Nicole Klein, Jorge Velez Juarbe, Tanja Wintrich, Liam J. Revell, and Lars Schmitz; Early giant reveals faster evolution of large body size in ichthyosaurs than in cetaceans. Science, 24 Dec 2021 Vol 374, Issue 6575 DOI: 10.1126/science.abf5787