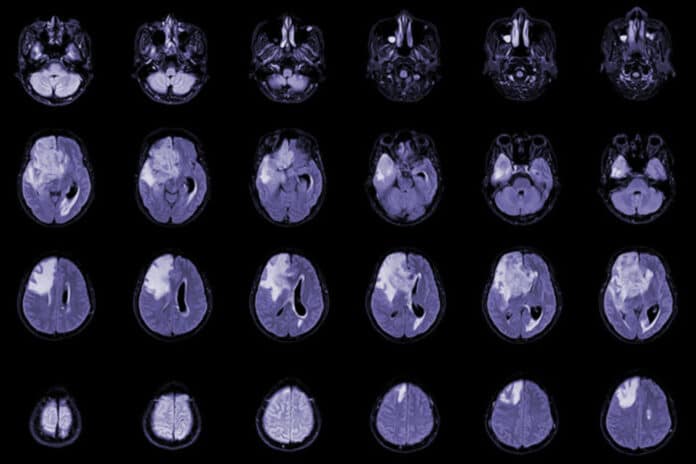

Glioblastoma is an aggressive type of cancer that can occur in the brain or spinal cord. Patients with glioblastoma receive treatment that frequently leads to the unfortunate side effect of low white blood cell counts, i.e., severe and prolonged lymphopenia. It has been associated with worse survival, but its underlying biological mechanism is poorly understood.

The latest study headed by the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis identifies at least one cause of glioblastoma patients’ low white blood cell counts. They even discovered a potential treatment strategy that improves survival in mice.

Co-corresponding author Jiayi Huang, MD, an associate professor of radiation oncology and co-clinical director of the Brain Tumor Center at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine said, “We know patients who develop low lymphocyte counts do worse than average. To improve their outcomes and extend their lives, we needed to understand what is causing these low levels of white blood cells and how it contributes to worse survival.”

Scientists collected and examined blood samples taken from glioblastoma patients for the study. About half of the patients developed low white blood cell counts following treatment.

Scientists noticed a significant increase in myeloid-derived suppressor cells in those that developed lymphopenia. These types of cells are known for suppressing the immune system. The scientists subsequently demonstrated a link between the suppression of white blood cells and the rise in myeloid-derived suppressor cells by irradiating the tumor in mice trials.

Senior corresponding author Dinesh Thotala, Ph.D., who conducted this work at Washington University and is now with the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, said, “We wanted to find out if we could block these myeloid-derived suppressor cells using an inhibitor to improve treatment response to radiation. We tested two inhibitors separately with radiation and found a significant improvement in survival in multiple mouse models of this cancer.”

Scientists also found that, on average, all of the mice with glioblastoma that received radiation died by day 40. Of the mice that received either inhibitor plus radiation, 50% to 60% were still alive at day 120, when the experiment ended.

One inhibitor, CB1158, is being tested in a clinical trial to treat solid tumors, such as colorectal, lung, and bladder malignancies. It belongs to a class of medications called arginase-1 inhibitors. The second medication is tadalafil, a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor authorized by the Food and Drug Administration to treat various ailments, such as pulmonary hypertension and erectile dysfunction.

Huang said, “The myeloid-derived suppressor cells have normal functions in the body. During pregnancy, the body makes these cells suppress the immune cells, so it doesn’t attack the embryo or fetus.”

“But glioblastoma takes this normal process and exploits it for its purpose. Furthermore, radiating the tumor triggers the body to create massive quantities of these cells, leading to low white blood cell counts in our patients, sometimes for many months. Our work suggests that targeting those cells in combination with radiation may be a new, exciting strategy to improve the treatment of glioblastoma.”

To further confirm their findings, the scientists have conducted a small clinical trial that combined tadalafil with standard radiation for patients with glioblastoma.

Journal Reference:

- Subhajit Ghosh et al. Radiation-induced circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells induce systemic lymphopenia after chemoradiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma. Science Translational Medicine. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn6758