The World Health Organization states that major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most common cause of disability worldwide, with a lifetime prevalence of close to 20%.MDD affects one in ten individuals at any given time. The Medical and non-medical costs associated with MDD are estimated at nearly $300 billion per year in the United States alone. The current COVID-19 pandemic suggests that depression is a common consequence of those contracting moderate to severe forms of the disease.

Currently, antidepressant treatment is available, which is beneficial. But, it is not always effective. Also, it takes months to work, and approximately one-third of treated subjects do not achieve remission.

Further, the adverse events associated with antidepressants may occur early in the treatment course and contribute to medication non-compliance before the drugs have had a chance to achieve clinical efficacy.

Given the substantial medical, economic, and social costs involved with MDD, there is a clear need for a practical and quantitative method to differentiate and optimize treatment options as early as possible.

Now, researchers are one step closer to developing a blood test that provides a simple biochemical hallmark for depression and reveals the efficacy of drug therapy in individual patients.

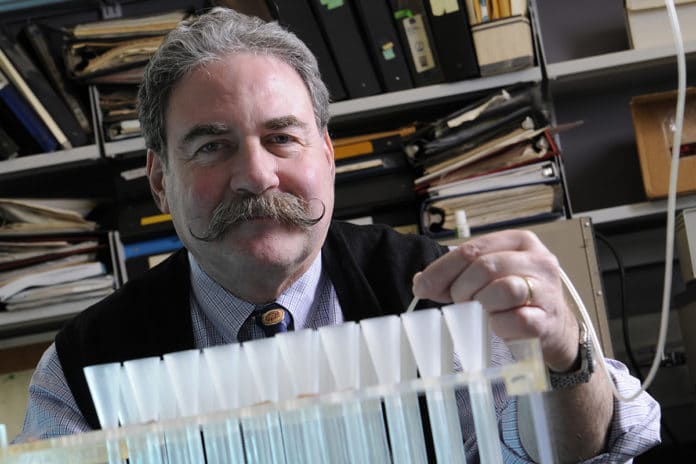

Published in a new proof of concept study, researchers led by Mark Rasenick, University of Illinois Chicago distinguished professor of physiology and biophysics and psychiatry, have identified a biomarker in human platelets that tracks the extent of depression.

The research builds on previous studies by several investigators that have shown in humans and animal models that depression is consistent with decreased adenylyl cyclase — a small molecule inside the cell that is made in response to neurotransmitters such as serotonin and epinephrine.

“When you are depressed, adenylyl cyclase is low. The reason adenylyl cyclase is attenuated is that the intermediary protein that allows the neurotransmitter to make the adenylyl cyclase, Gs alpha, is stuck in a cholesterol-rich matrix of the membrane — a lipid raft – where they don’t work very well,” Rasenick said.

The new study, “A Novel Peripheral Biomarker for Depression and Antidepressant Response,” published in Molecular Psychiatry, has identified the cellular biomarker for translocation of Gs alpha from lipid rafts. The biomarker can be identified through a blood test.

“What we have developed is a test that can not only indicate the presence of depression but it can also indicate therapeutic response with a single biomarker, and that is something that has not existed to date,” said Rasenick, who is also a research career scientist at Jesse Brown VA Medical Center.

The researchers hypothesize they will use this blood test to determine if antidepressant therapies are working, perhaps as soon as one week after beginning treatment. Previous research had shown that when patients showed improvement in their depression symptoms, the Gs alpha was out of the lipid raft. However, in patients who took antidepressants but showed no improvement in their symptoms, the Gs alpha was still stuck in the raft — meaning simply having antidepressants in the bloodstream was not good enough to improve symptoms.

A blood test may show whether or not the Gs alpha was out of the lipid raft after one week.

“Because platelets turn over in one week, you would see a change in people who were going to get better. You’d be able to see the biomarker that should presage successful treatment,” Rasenick said.

Currently, patients and their physicians have to wait several weeks, sometimes months, to determine if antidepressants are working, and when it is determined they aren’t working, different therapies are tried.

“About 30% of people don’t get better — their depression doesn’t resolve. Perhaps, failure begets failure, and both doctors and patients make the assumption that nothing is going to work,” Rasenick said. “Most depression is diagnosed in primary care doctor’s offices where they don’t have sophisticated screening. With this test, a doctor could say, ‘Gee, they look like they are depressed, but their blood doesn’t tell us they are. So, maybe we need to re-examine this.”

Limitations of the study:

The treatment was open-label and lacked a treatment group, so it could not establish that antidepressants specifically caused the changes in PGE1 stimulated adenylyl cyclase as opposed to non-specific improvements in depression severity.

There were no medication adherence measures taken in this study, and researchers cannot be sure if subjects took the prescribed antidepressants for the duration of the 6-week trial, if at all. It is well established that many subjects do not comply with treatment requirements during a clinical trial and that non-adherence can affect the study outcome.

The clinical metrics and Gsα stimulation assessments were only done at pre-and post-treatment, with no interim measures to determine the trajectory of the clinical response or its relationship to increases in Gsα stimulated adenylyl cyclase.

Journal Reference

- Targum, S.D., Schappi, J., Koutsouris, A. et al. A novel peripheral biomarker for depression and antidepressant response. Mol Psychiatry (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-021-01399-1