Bacteria frequently take part in ‘warfare’ by discharging toxins or different molecules that harm or slaughter contending strains. This war for assets happens in most bacterial networks, for example, those living normally in our gut or those that cause diseases.

And in addition, creating toxins that specifically execute their rivals, bacteria can discharge toxins that can go about as ‘provoking agents’. These toxins influence different strains to build their aggression levels by boosting their poisonous reaction.

In another investigation, drove by Imperial College London and the University of Oxford, specialists utilized a combination of analyses and numerical models to perceive what happens when bacteria incite their rivals.

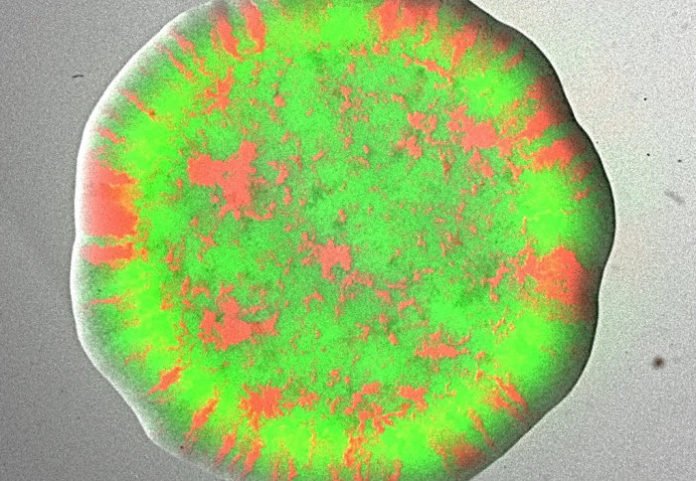

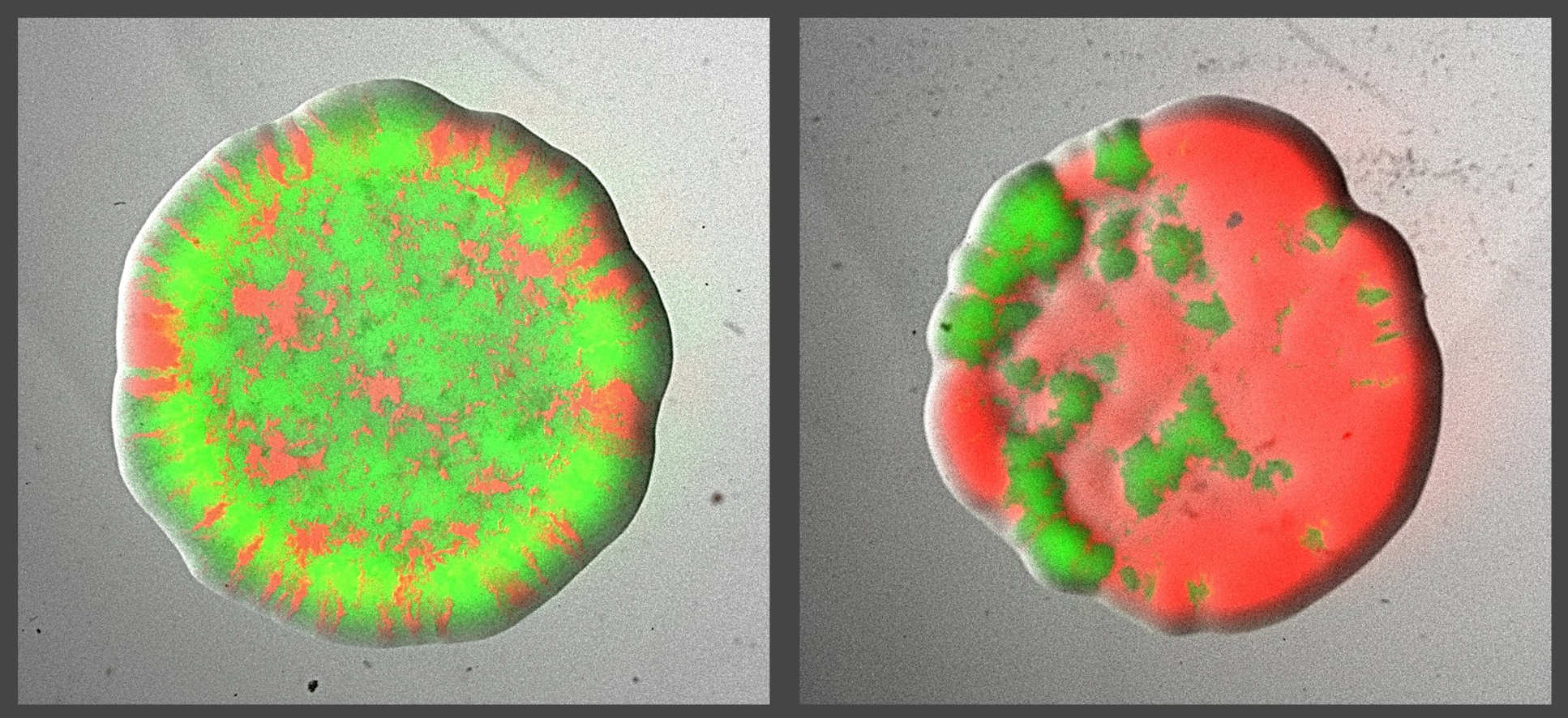

Scientists discovered that when used against a single competitor, provocation backfires: the provoked strain mounts a strong toxic counterattack and harms the provoking strain.

In any case, when there is at least three strains exhibit, provocation causes the other contending strains to expand their aggression and attack each other. This can prompt the contenders wiping each other out, particularly when the inciting strain is protected from, or impervious to, their poisons.

Senior author Dr. Despoina Mavridou, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial, said: “This behavior is strongly reminiscent of the human ‘divide and conquers’ strategy, famously delineated by Niccolò Machiavelli in his book The Art of War and shows that bacteria are capable of very elaborate warfare tactics.”

Lead author Dr. Diego Gonzalez, from the University of Lausanne, said: “We could envisage exploiting provocation in alternative antimicrobial approaches. For example, exposing established bacterial communities to low levels of known antimicrobials could promote warfare and cross-elimination of different strains.”

Scientists noted that the approach holds the potential to be used in eradicating safe biofilms – layers of bacteria that shape for instance in modern water pipes and are difficult to evacuate. It could likewise be utilized to treat some bacterial contaminations if the synthesis of the bacterial network in charge of the disease is outstanding.

Dr. Mavridou added: “By provoking other strains to attack each other, the toxin of the provoker is more effective than what would be expected based on its real toxicity. Using toxin-mimicking chemicals, we could potentially manipulate microbial aggression to our own benefit.”

The study’s other authors are Akshay Sabnis from the Medical Research Council Centre for Molecular Bacteriology and Infection at Imperial and Professor Kevin Foster from the Department of Zoology at the University of Oxford.

Scientists have reported their study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.