Metal-poor stars—containing less than one-thousandth the amount of iron found in the Sun—are some of the Galaxy’s rarest objects. The study of these stars’ orbits has found that some of them travel in previously unpredicted patterns.

According to scientists, theories on how the Milky Way formed are set to be rewritten following discoveries about some of its oldest stars’ behavior.

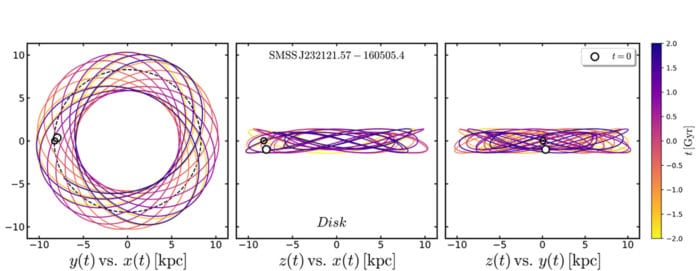

In a study by the ARC Centre of Excellence for All-Sky Astrophysics in 3D (ASTRO 3D), scientists studied 475 Metal-poor stars. 11% of stars orbit in the almost flat plane that is the Milky Way’s disc.

Past studies have suggested that metal-poor stars were solely limited to the Galaxy’s halo and bulge, yet this study uncovered a huge number orbiting the disk itself.

The Sun also orbits inside the disk, which is why it shows as the comparatively thin, ribbon-like structure effectively noticeable from Earth in the night sky. We see it edge-on.

Lead author Giacomo Cordoni from the University of Padova in Italy said, “In the last year our view of the Milky Way has dramatically changed.”

“This discovery is not consistent with the previous Galaxy formation scenario and adds a new piece to the puzzle that is the Milky Way. Their orbits are very much like that of the Sun, even though they contain just a tiny fraction of its iron. Understanding why they move in the way that they do will likely prompt a significant reassessment of how the Milky Way developed over many billions of years.”

Scientists identified the ancient stars using three very high-tech pieces of kit: ANU’s SkyMapper and 2.3-meter telescopes, and the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite.

The result —crunched by analysts from Australia, Italy, Sweden, the United States, and Germany—found that the orbits of ancient stars fell into various examples, everything except one of which coordinated past forecasts and observations.

As expected, many of the stars had generally spherical circles, clustering around the Galaxy’s stellar halo— a structure thought to be in any event 10 billion years old.

Others had uneven, and “wobbly” paths thought to be the consequence of two cataclysmic collisions with smaller galaxies that happened in the distant past—crating structures known as the Gaia Sausage and the Gaia Sequoia.

Some stars were orbiting retrograde—viably going the wrong way around the Galaxy—and a few, around five percent, appeared to be in the process of leaving the Milky Way altogether.

And then there were the remaining 50 or so, with orbits aligned with the Galaxy’s disk.

Cordoni said, “I think this work is full of important and new results, but if I had to choose one, that would be the discovery of this population of extremely metal-poor disk stars. Future scenarios for the formation of our Galaxy will have to account for this finding—which will change our ideas quite dramatically.”

Journal Reference:

- Cordoni et al. Exploring the Galaxy’s halo and very metal-weak thick disk with SkyMapper and Gaia DR2, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2020). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/staa3417