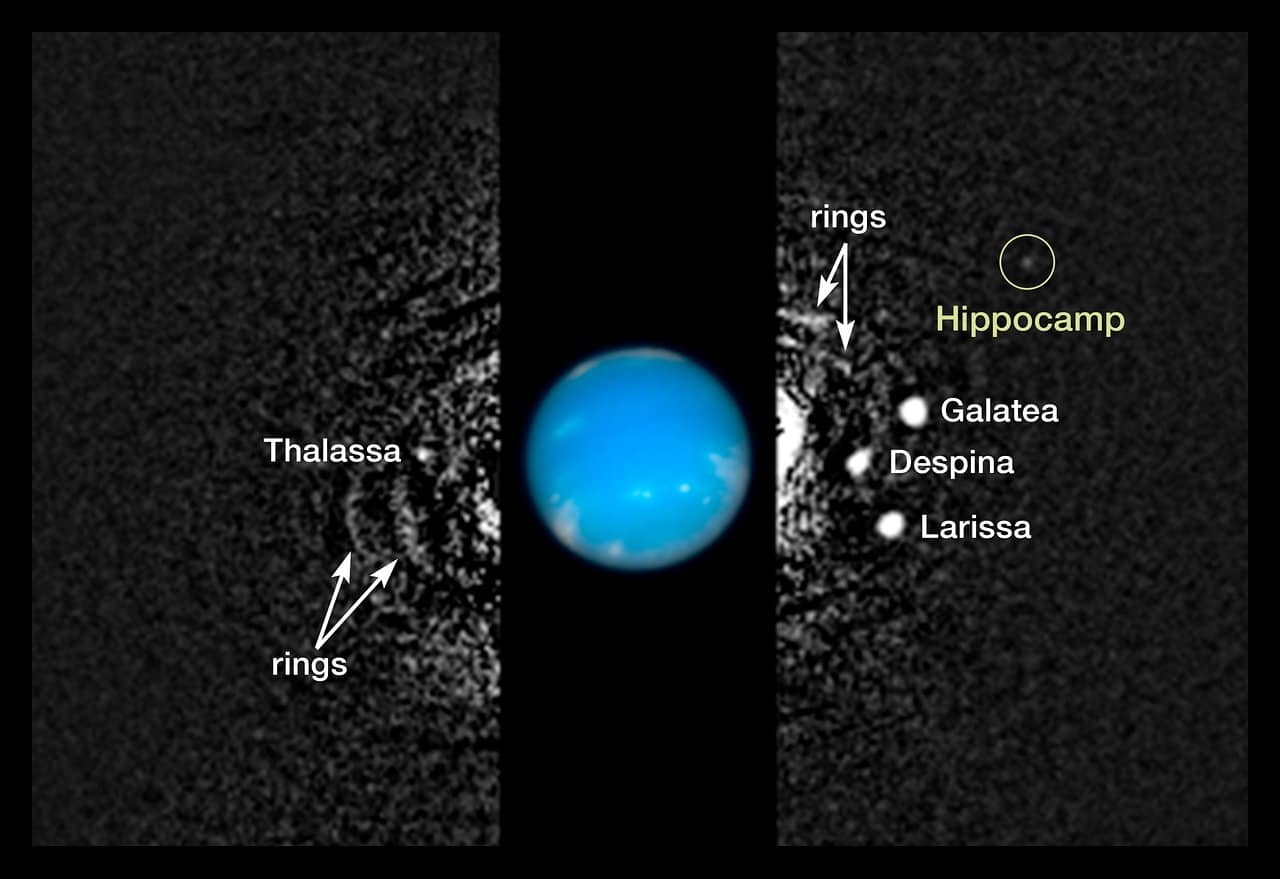

Astronomers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, along with older data from the Voyager 2 probe, have revealed more about the origin of Neptune’s smallest moon. The moon, which was discovered in 2013 and has now received the official name Hippocamp, is believed to be a fragment of its larger neighbour Proteus.

A team of astronomers, led by Mark Showalter of the SETI Institute, have used the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope to study the origin of the smallest known moon orbiting the planet Neptune, discovered in 2013.

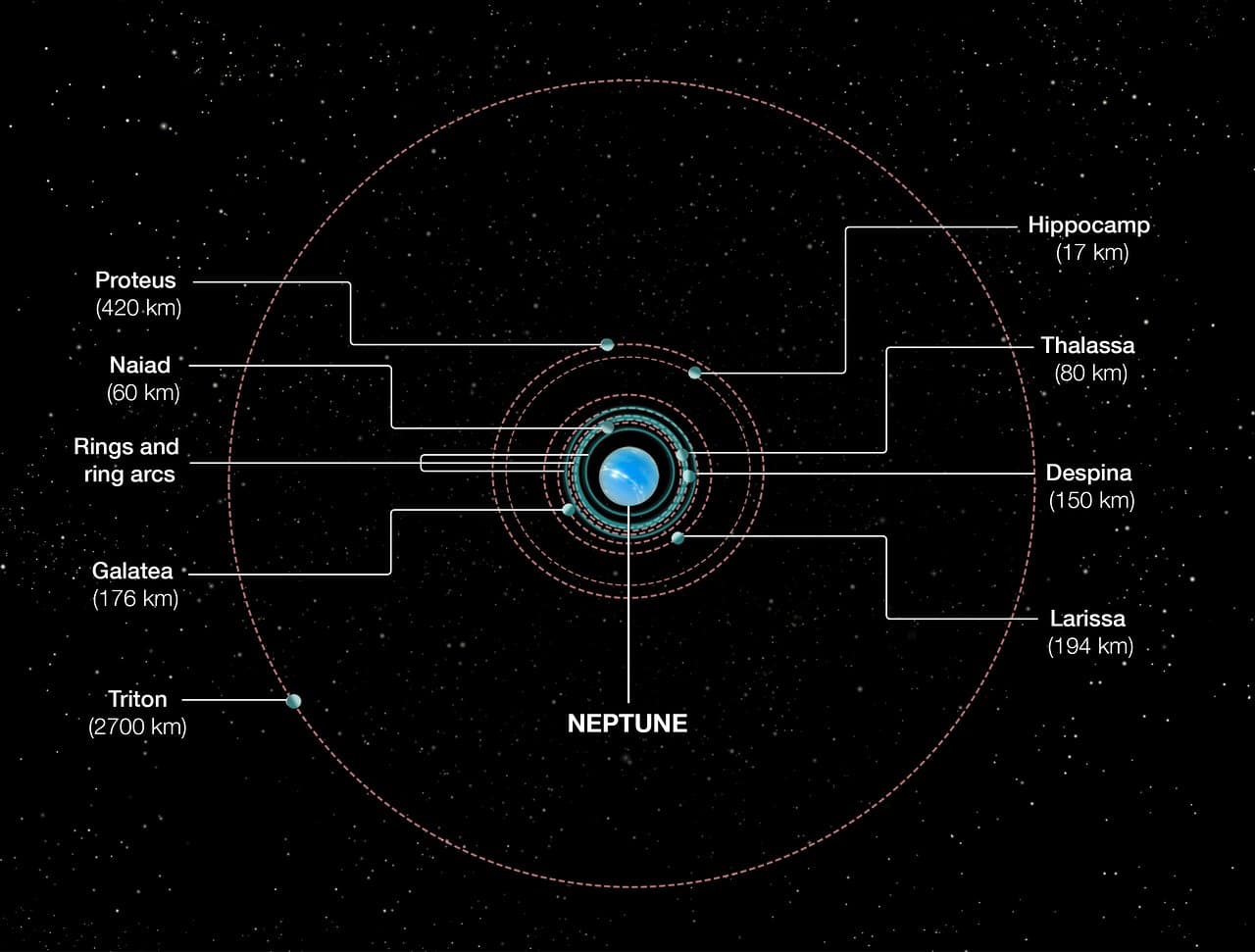

“The first thing we realised was that you wouldn’t expect to find such a tiny moon right next to Neptune’s biggest inner moon,” said Mark Showalter. The tiny moon, with an estimated diameter of only about 34 km, was named Hippocamp and is likely to be a fragment from Proteus, Neptune’s second-largest moon and the outermost of the inner moons. Hippocamp, formerly known as S/2004 N 1, is named after the sea creatures of the same name from Greek and Roman mythology.

Credit: NASA, ESA, and M. Showalter (SETI Institute)

The orbits of Proteus and its tiny neighbour are incredibly close, at only 12 000 km apart. Ordinarily, if two satellites of such different sizes coexisted in such close proximity, either the larger would have kicked the smaller out of orbit or the smaller would crash into the larger one.

Instead, it appears that billions of years ago a comet collision chipped off a chunk of Proteus. Images from the Voyager 2 probe from 1989 show a large impact crater on Proteus, almost large enough to have shattered the moon. “In 1989, we thought the crater was the end of the story,” said Showalter. “With Hubble, now we know that a little piece of Proteus got left behind and we see it today as Hippocamp.”

Credit: NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI)

Hippocamp is only the most recent result of the turbulent and violent history of Neptune’s satellite system. Proteus itself formed billions of years ago after a cataclysmic event involving Neptune’s satellites. The planet captured an enormous body from the Kuiper belt, now known to be Neptune’s largest moon, Triton. The sudden presence of such a massive object in orbit tore apart all the other satellites in orbit at that time. The debris from shattered moons re-coalesced into the second generation of natural satellites that we see today.

Later bombardment by comets led to the birth of Hippocamp, which can therefore be considered a third-generation satellite. “Based on estimates of comet populations, we know that other moons in the outer Solar System have been hit by comets, smashed apart, and re-accreted multiple times,” noted Jack Lissauer of NASA’s Ames Research Center, California, USA, a coauthor of the new research. “This pair of satellites provides a dramatic illustration that moons are sometimes broken apart by comets.”